Why is everyone in the world over-interpreting their data this week and coming for women in science? How can authors get all the way through graduate school and still not understand how not to over-interpret their data?

Perhaps in an effort to cause hypertension and make the blood vessels in my head explode, a reader of the blog sent me another article on women in science, published this week. Titled, The confidence gap predicts the gender pay gap among STEM graduates, the authors of this paper from PNAS speculate that “cultural beliefs about men as more fit for STEM professions than women may lead to self-beliefs that affect pay”. This implies causation and the ultimate causative step is that women’s self-beliefs impact pay.

I don’t understand this week’s trend to blame women for our own inequity. We are under-cited because we choose to work with other women or have the audacity to mentor other women. We are under-paid because we lack self-confidence. If only we had the good sense to publish with men and be more self-confident, we’d solve all of the world’s problems.

Ladies, if we can’t get our shit together, we might as well give back the vote. We clearly don’t deserve it.

This new paper seems interesting at first glance, but quickly reveals itself to be flawed. The authors surveyed 559 men and woman and asked them questions related to their self-confidence, income, and beliefs about pay equity and workplace culture. Using mediation modeling techniques, the author find an association between reported self-confidence and income.

These aren’t horrible questions and the data themselves do not appear to be problematic. It’s the authors’ constuct of their model and interpretation of their results that is problematic.

Women earn less than men in their initial jobs. We find no evidence that this gap in pay is due to men’s having stronger interests in high-paying jobs than women, or because women have preferences for the culture of workplaces that might correspond with lower pay. Rather, we find that women have lower levels of self-efficacy than men, and that self-efficacy mediates the relationship between gender and initial salaries.

The data show that women in STEM both earn less and are less confident. This is no shock, particularly to actual women in STEM. The type of model the authors performed to link these is called a mediation model. Mediation models attempt to link two variables through a third variable – the mediating or intervening variable. We use them in physiology and health behavior/promotion research to try to understand how two phenomena may be linked, mechanistically. We can then go back and probe these mechanisms, experimentally. They have some pitfalls and their validity is always limited when they are not validated with a well-control interventional design. But, to focus on the paper alone…

In order to strengthen the argument that a mediator is causative and not merely correlative, the model should generally meet three criteria. The must show:

- Empirical association

2) Temporal Precedence

3) Nonspuriousness

Empirical association is the requirement that two things be numerically related (ie, correlated). We see these types of associations all the time in the scientific literature. Empirical association is relatively straight-forward, here. The variables and the mediator – gender and self-efficacy and pay and self-efficacy, are correlated.

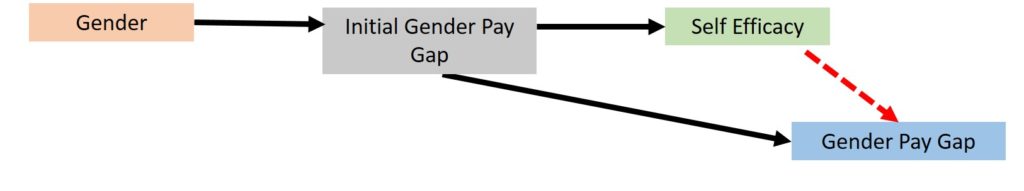

The problems lie in temporal precedence and nonspuriousness. The strength of the model is increased when you can demonstrate that the mediator preceded the outcome variable. Otherwise, the following two scenarios are equally probable:

The authors tried to address this by administering their survey twice – once while the participants were in college and once after graduation. I’ve read the survey in the appendix and their first job is defined as their first job after earning a bachelor’s degree. I don’t see evidence that they asked about previous work or earning experience. It is unlikely that this is their first job. Up to 70% of college students work while they are in college. There are less data for younger earners, but gender-based pay gaps are present among non-degree holders.

Another requirement for these models is “nonspuriousness,” meaning the correlation cannot be the result of some unidentified variable that truly contributed to the outcome variable while the mediator was simply a spurious (ie, false) intermediary of the true effect. If we take the supposition that many of the students in the study worked in high school, I can create an equally valid model that invalidates the authors’ model based on the principles of temporal precedence and nonspuriousness.

It is likely that many students had a job while in high school or college and we don’t know where the low self-efficacy falls relative to the actual first job. It is also possible that a pay gap in the initial work experience contributes to both lower self-efficacy and to a perpetuating gender pay gap. In that case, the relationship between self-efficacy and the first post-bachelors job is parallel and not serial (ie, causative). They trend together because they are linked to a common event (a pay gap in the first pre-bachelors job), but the implication of causation is spurious.

It is alternatively possible that the principle of nonspuriousness is violated thusly…

In this model, decreased self-efficacy precedes the pay gap in time, but they are not linked causatively. They correlate together because they are still tied to a common variable. But, maybe they are still mediated by a mediator? I’ll expand my model one more time to drive home the point…

To give no lip service to the fact that this is an equally probable model is just a sin. Maybe we feel bad about ourselves and make less money because women are undervalued in science. Maybe we don’t need to fix women. Maybe we need to fix how women’s contributions are regarded.

Still, the authors conclude…

In closing, there are several important practical implications from this study. Our results highlight the importance of career guidance as well as possibly internships and co-ops to strengthen students’ self-assessments and provide stronger bridges to engineering and CS jobs with higher pay (45). Our results also ask practitioners and industry experts to reconsider hiring practices that overemphasize confidence in one’s ability as an indication of likely job success. Since self-perceptions may not accurately reflect technical ability and may correspond to gender, doing so may only stand to widen the gender pay gap.

We know nothing of the training environments these students come from or the hiring practices and policies of the employers that hired these professionals. We don’t know where educational experience and hiring practice fit in the model because that wasn’t tested, so it’s irresponsible to prescribe policy. Yet, these are the authors’ conclusions. Make more confident women. It reads like an self-validation of pre-conceived notions, held up by a problematic model.

It’s hard to read these things this week, my darlings. Stay strong.