What’s the Word on Jill Abramson?

We previously mentioned some of the problems with the “ban bossy” movement – namely, that it focuses on a single word that’s used pejoratively, and doesn’t actually work to create spaces where it’s acceptable, even encouraged, for women to be assertive and confident. Recently, The New York Times Executive Editor Jill Abramson was suddenly fired following her inquisition into her pay rate. Her dismissal brings the need for assertive women into sharp relief, and calls into question the Times’ stated commitment to creating an egalitarian environment.

Allegedly fired for poor management, Abramson had brought eight Pulitzers and new revenue growth to the times, and had worked hard to appoint more female staffers to high-profile roles. She was replaced by Managing Editor Dean Baquet, who punched a wall during an argument with Abramson last year but is still described as unfailingly polite. (Go figure.)

Much of the reaction to the dismissal has been more or less one of disbelief – not so much that Abramson would be fired, but that she would be fired so publicly, and with framing that so clearly evokes the spirit behind the “ban bossy” campaign. A few of the terms that were used by Times boss Arthur Sulzberger to describe Abramson to explain her firing include:

- difficult (women should be easy!)

- polarizing (women should bring people together!)

- mercurial (women should be predictable!)

- undiplomatic (women should be diplomatic!)

- pushy (women should be pushovers!)

She’s also been called the following, by others, each of which also has its own corollary in terms of how women are expected to behave:

- stubborn (women should be flexible!)

- condescending (women should be condescended to!)

- intimidating (women should be intimidated!)

- brusque (women should be considerate!)

- remote (women should be friendly!)

- a source of widespread frustration and anxiety (women should promote ease and calm!)

- uncaring (women should be nurturing!)

- difficult (women should be easy!)

In contrast, here are a few things that actual Times employees and Abramson’s colleagues reportedly said about the firing, which suggest it may not have had roots in her managerial style after all, as Sulzberger claims:

as well as just a few things people have said about Abramson, in general:

- she works incredibly hard

- forceful and fearless

- cares passionately

- a brilliant journalist

- awe-inspiring

- pre-Sheryl Sheryl [Sandberg]

- able to work across genders

- one of the boys (!)

- loyal

- warm

- brilliant

- behaved honorably

- terrific gut instincts

Re/code founder Kara Swisher pointed out that gendered expectations of Abramson may not have ended with the decision to get rid of her. To the contrary: “Abramson’s toughness seems to be the central reason that Sulzberger decided to dispense with her, first by asking her to do the nice-girl thing and resign and, when she refused, by firing her in perhaps the most awesome example of PR gone very, very bad.” By not being pliant, Abramson subjected herself to worse treatment.

New details have emerged suggesting that Abramson was fired largely for attempting to hire someone (a woman!) and not properly informing Baquet and other Times staffers about it as she said she’d done. But if that’s the case, why not just say so? Firing someone – a journalist, no less – for misrepresenting the facts about a hiring process seems an incredibly valid thing to do. Firing someone for vague reasons related to management style, particularly when those reasons ring rather sexist, seems less valid – especially when the woman being fired has just inquired about her pay rate compared with that of male employees, and double especially when the person doing the firing has summarily dismissed high-profile female employees in the past in similarly questionable situations.

Sulzberger also presided over a similarly abrupt 2011 firing of Times CEO Janet Robinson. Credited with helping lead the charge to make the Times a national paper of record, Robinson was called “The Nanny” by some Times staffers for her role as newsroom caretaker, giving us yet another gendered take on women at the paper. She was fired “out of the blue” apparently largely due to conflicts with Sulzberger’s romantic interest at the time, which may have been a valid reason (though unlikely), but also plays into expectations that powerful women will conflict with one another rather than with the men around them (yet still be subject to retribution from those men).

Although Robinson was fired, her insistence on a paid Times model seems to have led to more revenue for the company by now. In fact, current Times CEO Mark Thompson (a man who’s clashed with Abramson as well) called the paywall “the most important and most successful business decision made by The New York Times in many years.” And, as mentioned, Abramson’s Times has earned eight Pulitzers and outperformed the S&P 500. So why does Arthur Salzberger love firing women who do a great job?

(More to the point, why does he not only love firing women, but colluding with other men to do it? Sulzberger apparently lunched with Abramson replacement Baquet before Abramson’s firing, and was goaded into dropping Robinson by his cousin Michael Golden, who butted heads with Robinson over several issues, including selling the Boston Globe. Does Sulzberger ultimately trust and listen to male subordinates more than female leaders?)

Maybe Sulzberger expects women to be subservient to his agenda for the paper, which would make being an assertive woman grounds for firing at the Times. That plays into the next step in gender and racial equality, as mentioned by Teju Cole: ownership. Why stop at editing? Why shouldn’t a woman be in charge not only of the paper, but of the people who run it, as owner of the Times?

Problems with female authority don’t end in New York. Women CEOs get fired nearly 50 percent more often than men. But that’s largely because women are often brought into the position during crisis situations, which are more difficult to handle. If the female CEO fails to turn around a struggling company, the white dude status quo is often restored (and white dudes can take the credit for the eventual results of women’s work – like with Robinson’s Times paywall, perhaps). Female CEOs are also more likely to be brought in from outside the company than male CEOs, who more often come from within.

Dean Baquet, former managing editor and now executive editor, has been promoted from within, like many Times leaders. He’s been called, among other things:

Not only do these descriptors stand in stark contrast to many used to describe Abramson, they also eerily conform to another set of expectations that our society has – of black people. Society likes black people when they’re “good negroes” who defer to authority, who are polite, subtle, subservient. Society doesn’t like black people when they’re strong or outspoken. If Abramson was dumped for being too difficult, perhaps Baquet has been promoted for being (too?) pliable.

As journalist Ann Friedman pointed out in response to the events at the Times, “Women never know whether they’re being met with a hostile reaction because of their performance — something that they can address and change — or because of both male and female colleagues’ internalized notions of how women should behave.” Because we don’t know for sure what happened here, we need to think about how these internalized notions might have been involved. Maybe there was truly no sexism involved in Abramson’s firing – hard to believe, but possible. But there are sexist (and racist) expectations involved in how we describe people and what we expect of them, and only by actually thinking about those expectations and taking them apart – rather than denying they exist – can we ever overcome them.

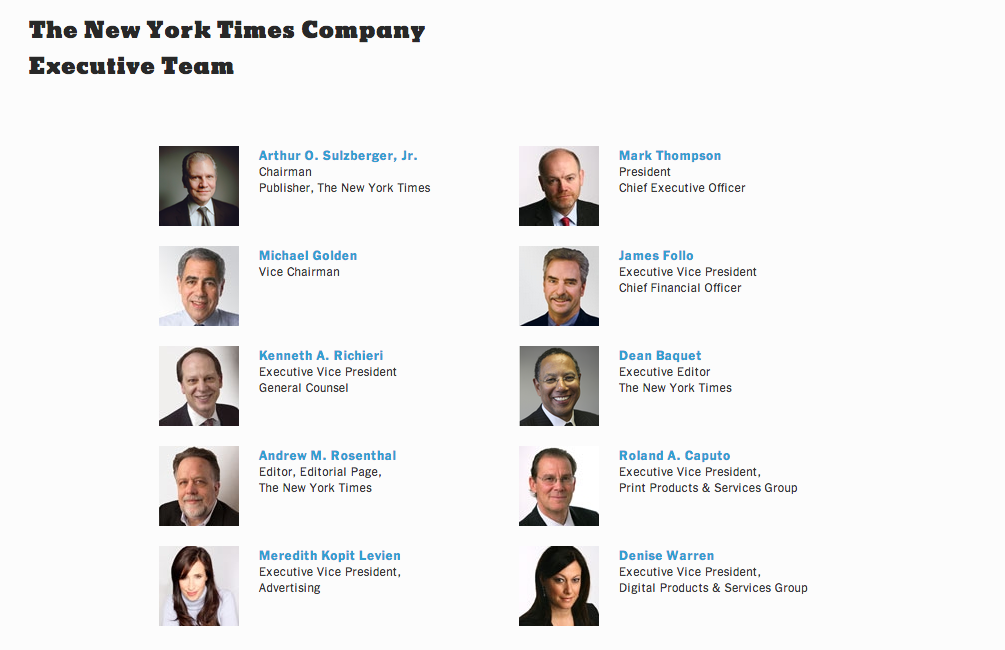

If you can’t see the featured image, here is is in full – The New York Times Company’s leadership, now 20 percent women.

A year ago, Friedman wondered what it would be like if Jill Abramson were a man. Maybe now we should add to the list that she’d still have a job.

Fired for being too good at her job.

Remember, kids! Mediocrity is the only way to get ahead in life! Don’t make waves!

No. You are ignoring the sexism. If she had been male, the very things she was criticized for would have been considered assets.

Mediocrity would not have helped here. The problem is, as the OP points out, that the characteristics that were required for her to be qualified for her job are also the characteristics that women are forbidden to have. She (like any woman in that position) was in a double-bind: if she acted competently enough to not be fired, she would be fired for being unwomanly. If she acted womanly enough not to be fired, she would have been fired for incompetence.

Not that it surprises me that a bastion of the Establishment like the NYT would be old-school sexist to the core.

I would like to point out that, to some degree, a few of these words are nothing more than post-hoc justifications used to explain any termination of a CEO. It is certainly true that while a person, man or woman, is successfully filling a leadership position, certain traits will be described positively, and when the same person is terminated (for just cause or not), those same traits will become negatives. “Strong” becomes “polarizing”; “Determined” becomes “stubborn”; etc. These are the common characteristics of people who rise to the levels of CEOs and presidents, and thus, when they fail (or are perceived to have failed), they are the traits that can be re-characterized as negative traits so that the public sympathizes. I’m not sure they tell us much about how the CEO is actually perceived while he or she is doing his or her job.

That’s not to say that sexism isn’t a huge problem in how women in leadership positions are perceived, and it certainly looks like the Times is going to have a hard time convincing us that sexism didn’t play a significant role here. But I’d bet if we went back to the articles describing Abramson when she was given the job, they would describe the same person, but would use the euphemistic descriptors instead of the pejoratives.

On the other hand, I don’t think I’ve ever heard the word “pushy” used to describe a male at any age level or job title. I guess maybe I’ve heard of “pushy” salesmen, but never has that term been applied to a professional male that I can remember. “Mercurial” and “difficult” are also pretty rare descriptors for the terminated male CEO, and I don’t think anyone has ever been concerned with whether a male CEO was “caring” or not (even after he was discharged). So the point is the same — it is easier to degrade a female CEO after she is terminated by using a wide-range of dog-whistle type criticisms that don’t even really matter to the position of CEO.

Jill Abramson will share the full story in time but clearly we have not been given an honest reason from the times. Its not just pay, bonus and stock/options, its sexist nonsense coupled with news related reasoning to fire her.

Why? Liberals don’t like dem scandals any more than conservatives like gop scandals. Problem is both sides collaborate to cover up and in recent years more and more scandals take long to develope to fruition. Jill Abramson isn’t obedient and wanted to do her job, no matter the scandal or whatever, section A of the Times covered all the news that’s fit to print….except the stories they have chosen to ignore that later embarrassed the Publishers family. That list became longer with former Bill Keller and Abramson is no Keller plus she wanted to serve the country, not either party!!!! That’s the key to why she was fired, its not just pay its the news.

Women have a right to be as arrogant as men, take it from a man, we are all created equal, what part of equal doesn’t publisher Arthur Ochs Sulzberger understand.