The COVID-19 Vaccine is 95% Effective. What Does That Mean? And Why is Herd Immunity via the Vaccine Better than Just Getting the Virus?

Great news has been released in the past two weeks. There are multiple vaccines that are emerging and preliminary results (from Phase III clinical trials) show that at least two are 95% effective. But what exactly does that mean? And why is it better to get the vaccine instead of just getting COVID-19 out in the wild, besides the obvious reasons?

Specifically, what prompted me to write this post was that my fellow Skepchick Jamie Bernstein had some questions, paraphrased below:

- If a vaccine is stated to be 95% effective, does that mean only within the ideal conditions of the study (i.e. in a world where everyone is social-distancing and wearing masks)? So, in the real world, would it still be as effective?

- Does “95% effective” mean that you have a 95% chance of not getting the virus every time you are exposed?

Let me explain how they derive the 95% effectiveness. Tens of thousands of people were enrolled in each study (I believe they tried to recruit in cities and other places that were possible hot-spots to maximize exposure to minimize the total time needed for the trial). Half of the people got the vaccine, the others got a placebo shot. Then, we just wait and see who gets sick. The FDA said the vaccine trial needs at least 165 people to get sick, which doesn’t seem like a lot but I don’t believe either trial has hit that number yet (with the way the cases are coming in though it might be soon). Then they see, of the people who got sick in the trial, how many received the vaccine? The number of people who got sick who didn’t receive the vaccine versus the ones who did is basically how you calculate effectiveness.

Specifically in the Moderna trial, there were 30,000 people enrolled, and there were 95 CONFIRMED positive cases (had at least 2 symptoms plus a positive test, and for Moderna they ONLY counted cases that were at least 14 days post the second shot, which was 28 days from the first shot, so PLENTY of time to have a proper immune response, since there is a lag time between when you take a vaccine and when your body is prepared). Out of the 95 people who got sick, only 5 had received the vaccine, so it is 94.7% effective.

Ideally, the participants are split up in the study such that the risk for everyone will be the same (I know they tried to recruit a diverse population too, including race, sex, age, but don’t know all of the details). So, even though many people wear masks and social distance, in a population that size, there are plenty that don’t adhere to those rules, at least not perfectly all the time.

Would the vaccine be less effective if we all weren’t wearing masks and distancing? Highly doubtful. Normally, your immune system is great at absolutely crushing antigens it has previously identified as hostile.

Let me explain a little about how your body makes antibodies:

There are immune cells that are patrolling your body at all times looking for things that are not identified as YOU (via proteins on the surface). When they find something, they take little pieces of it and send it through your lymph system to essentially the immune central processing unit. Imagine that the surface of an antigen is covered with one type of lock–what your body does is essentially generate every type of key in the universe and try it in the lock until one fits. And as soon as one does, your body scales up this reaction and generates MILLIONS of these keys (these are the antibodies), then releases them throughout your body, where they stick to the surface of the antigen, thus tagging it as “NOT YOU”. When the other immune cells see this tag, they just go out and kill anything with an antibody stuck to it. And even though your antibodies in the blood stream will fade over time, certain immune cells remain that will be able to identify this antigen should it ever darken your doorstep again.

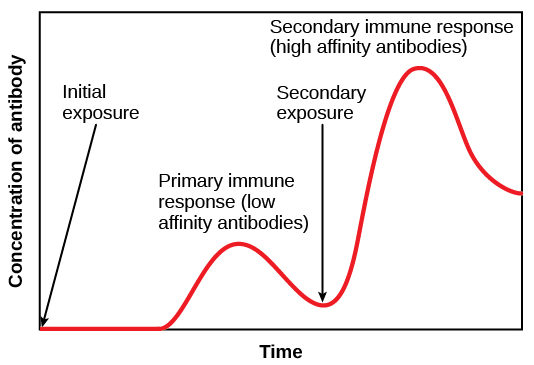

The graph below shows you the difference in response during a normal immune reaction. The time between initial exposure and the peak of the primary immune response can be 7-14 days. The time between SECONDARY exposure and the peak of the secondary immune response is much shorter, approximately 1-3 days. (These times are approximate, each antigen generates a different reaction, but you get the general point.)

So once you are vaccinated, your body is very good at quickly generating that secondary immune response and that’s why you generally don’t get sick from the same antigen twice (barring immune system issues). Now, why do we have a flu vaccine every year? Because the proteins on the surface of the antigen mutate just enough to make your body have to re-generate all new antibodies. Some antigens change faster than others, especially if they are allowed to infect people unchecked.

Why don’t we just allow herd immunity to happen instead of the vaccine? I mean, of course we know that by allowing people to get sick, specifically with regards to COVID-19, that will overwhelm the hospital system and a lot of people would die needlessly. But there’s also another complication that isn’t as visible: the vaccine allows for a more controlled immune response and there is a much lower chance of you getting an immune disease. Earlier, when I said that your body generates antibodies (keys) to fit a lock on the surface of the antigen, well sometimes the antigen surface resembles something else inside of your body, and now in addition to crushing the antigen, your body is also attacking itself, which can cause some of these long-term COVID-19 effects that we are seeing (speculative but I’ve seen journal papers mentioning it). This concept is called “molecular mimicry” and it’s the same reason that you can get bitten by a tick, develop Rocky Mountain Fever, and then develop an allergy to red meat. Or you get a virus and get better but end up with Type I Diabetes because your body attacked pancreatic cells. And the final issue is that we don’t know the long-term effects of getting COVID-19, because who knows what could emerge years later.

A big exception to what I’ve said is this: we know how the immune system NORMALLY works. But we just don’t know enough to say how the reaction will be specifically with regards to the COVID-19 virus, and how long people will be immune for, etc. Ideally though, your immune system will react in a predictable way as with most things.

As you mention, the usual flu virus manages to mutate often enough that we need a new flu vaccine each year.

If the COVID-19 virus mutates enough that the vaccines currently in development don’t protect against it, do you have any idea how long it would take to develop a vaccine against the new (mutated) virus? (I’m hoping that the current development efforts would mean they’d have a head start on one for the new strain.)

It’s hard to say at this point. We have fine-tuned the process for making flu vaccines every year (including development and distribution). It just depends on which part of the virus mutates. Currently, there are multiple types of vaccines in development that cause patients to create antibodies against many types of surface proteins, so if a protein mutated, it might be possible that another vaccine would be ready to fill that gap. The top 2 vaccines target the spike proteins (the parts of the virus that stick out), and it’s possible that even if parts of the virus do change, some regions may stay more constant.

Unfortunately this virus is so new that we just don’t have enough data to give hard numbers. From my own perspective, I am feeling more optimistic about the vaccines (as long as we can figure out distribution).

Yes, the 95% figure relates only to a population who developed symptoms and tested positive over the period of the study which I believe is only a couple of months. Clearly the figures will change over a longer time period. I wonder how long that follow up period may be?

Hopefully then, the 95% figure will translate pro rata to a reduction in hospital admissions and in mortality – I wonder whether those endpoints will be recorded though?

One thing that is not being recorded though is the number of asymtomatic infections. We simply do not know that number.

The virus will probably continue to spread via asymptomatic carriers unless protective measures such as masks and social distancing are continued for a while, albeit with a greatly reduced mortality rate.

A certain end to the pandemic would require a Mark 2 vaccine which achieves complete sterilisation.

Some of these problems were addressed in a lecture by Prof Petrowsky of Flinders Medical Center Adelaide, the leader of a local vaccine development group

One thing I know about working in the pharmaceutical industry: all data will be tracked with regards to patient outcomes. In fact, in the US, it is required that if you work at a company that makes drugs, and you know someone using that drug who is talking about an adverse event (even in casual conversation) you have to report it back to your company.

The virus definitely can spread asymptomatically—hopefully we can reduce the spread and the symptoms though!

If Petrovsky is right and the vaccine creates a whole lot of asymptomatic spreaders, this has profound implications on the priorities of distribution.

If it were up to me, initially I would vaccinate those >60y and leave it at that.

This would be logistically straightforward, similar to the annual flu vax, and have the maximum effect on mortality, preventing 98% of deaths based on Australian figures.

Instead it seems rather a lot of vaccine will be used on medical staff, which may not have the desired effect of reducing transmission but will certainly prevent full immunisation of the aged group above.

ofc I can see that medical staff of all people need to be given a lifeline of some sort but again if it were me I would rather see the full impact on reduced hospitalisations as given by the scheme above.

btw there was a good vaccine Q&A from Austarlian experts today:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-12-05/covid19-vaccine-questions-approval-and-data-requires-patience/12950608

It seems Oxford/Astra Zeneca is the only vaccine trial where actual infections are tested and monitored.

Petrowsky claims that his vaccine candidate, which has passed Phase 1 clinical trials, is a sterilising vaccine.

By “sterilising” ofc I mean “completely cleanse the body of the virus”!

NOT “sterilise” in the human reproductive sense as is assumed by conspiracy theorists

https://twitter.com/Majeh19/status/1334447176852889604

The STUPID, it burns!