The Next Wave of this Public Health Crisis May Be Scarier Than COVID

Lessons from the Irish Potato Famine

There are a couple of things weighing on my mind today, as I continue to write and think about the current COVID-19 pandemic. First, I really need the media to give me a day off from debunking inflammatory headlines like “French researchers to test nicotine patches on coronavirus patients.” There is a lot of pseudoscience out there, even from people with “MD” or “PhD” after their names that sounds truthy and isn’t grounded in any actual data. This highlights the importance of journalists and science writers having a cache of respected experts on deck, particularly when this nonsense has not been through peer review. Folks, if you need some help, call me.

And, no Mr. President. You can’t treat COVID by injecting yourself with disinfectant or exposing yourself to UV light. Beyond that, I’m thinking a lot about what the future of health and medicine in the United States will look like in the next months to years. History has a lot to teach us, but they are potentially very harsh lessons.

Not long ago, a study was published in the journal Science that modeled how COVID-19 will spread in the population with differing degrees of social distancing and immunity. Many have interpreted this to mean that social distancing, to some degree, will need to continue until at least 2022. This has led to some very interesting conversations among my local physician colleagues who wonder how they will be able to treat their patients. Not COVID-19 patients. The patients they would normally see, if they had not been instructed to either practice via telemedicine or to defer seeing patients until after COVID-19 is “over”. There are many types of patients that are not currently being seen by their doctors because either their doctor has been asked to help treat COVID-19 patients, or they’ve been asked to keep patients away for fear of spreading the virus. I’m experiencing this, myself. Because I have reached my crone years, I have some arthritis in my back and need injections. I can’t take oral anti-inflammatories for long because of my stomach surgery. Our hospital isn’t allowing non-emergent procedures, so I’m waiting patiently. I’m also using the oral anti-inflammatories that may cause a dangerous stomach ulcer because I don’t have many other alternatives.

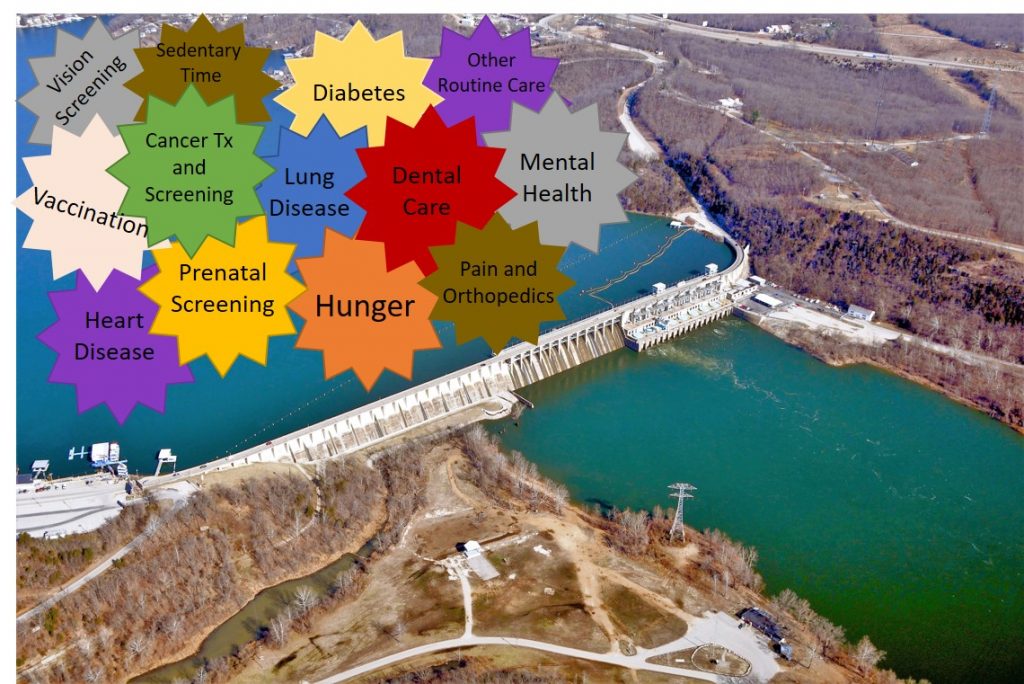

Think about all of the types of medicine that aren’t being practiced right now. People have less access to dental care, prenatal screening and well-child follow-up, followup for diabetes and cardiovascular disease, mental health treatment, and preventative medicine. Even the treatment of our cancer patients has changed, out of an abundance of caution because these patients may be immune-compromised. All of this is reasonable in the short term, given the limited hospital resources I discussed earlier. This does not mean that it’s not without a cost. The cost is the growing backlog of patients that are not receiving routine medical care. One of two things is going to happen to that growing backlog. Either the dam is going to break and those patients are going to flood the medical system or…

…they’re not. Recently, cardiologists and emergency department physicians reported seeing up to 50% fewer cases of heart attack and stroke in their hospitals. It’s certainly possible that people are having fewer heart attacks because they’re less stressed and happy in their house watching Tiger King on Netflix. It’s much more probable that people are avoiding medical treatment because they’ve been told to stay home and avoid the hospital, and they’re dying at home. President Trump says we have “one of the lowest COVID-19 related death rates in the world.” I have not seen any data on the aggregate US death rate and how this has been changed both by COVID-19 and social distancing measures. This is worth quantifying. It is definitely worth a bigger conversation about what we’re going to do with the patients not currently being treated, if continued social distancing is necessary.

There are also direct effects of social distancing on health. I hypothesize that there’s a dichotomous response and that both of these responses will have profound effects on public health. Some are fortunate enough to have kept their jobs during periods of social distancing. Their biggest challenges are deciding the time of day that it’s acceptable to start drinking and which snacks are the best for the new season of Ozark. I think a cold one and chips and queso are the best for watching Jason Bateman getting punched in the face. America must agree because alcohol sales and salty snack sales are up in the United States. Increased sedentary time, mental stress, increased alcohol use, and increased caloric intake are not good for long-term cardiovascular health. The alternative is equally as insidious.

The unemployment rate in the United States has surged, likely exceeding 15%. Government stimulus checks are enough to cover rent for many, but not much else. It’s likely that food insecurity and hunger are running rampant among the unemployed and under-employed right now. Starvation is also bad for cardiovascular health. Just ask the Irish.

In the 1840s, P. infestans (potato blight) ravaged Ireland’s potato crops. The pathogen destroyed half of Ireland’s potato crop, leading to rampant starvation and the death of nearly a million people.The impact didn’t end when the pathogen was contained. One of the most important lessons learned from the Irish Potato Famine is that hunger and starvation have negative physiological consequences that are transmittable to future generations. Descendants of people impacted by the famine have a two-fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease and an increased risk of mental health disorders. Once the damage is done, this impact isn’t offset by improving economic and psychosocial conditions. We can’t offset this devastation with money and resources. Trauma and starvation may create generational imprints by altering our DNA, allowing us to pass our trauma on to our offspring in the form of shortened life span and increased disease risk. Hunger and starvation are never short term problems. Any strategy that causes part of the population to go hungry is going to have important, long-lasting consequences. We don’t have good data on how much of the population is hungry because of social distancing measures.

It seems like every apocalypse movie starts with someone ignoring data from a scientist. This is exactly the right time to let scientists do their jobs and collect data. We’re learning a lot about this virus and those data are going to save us, not injecting yourself with disinfectant. But, lawmakers need to give scientists time to continue to collect data by providing information that informs policy and allows us to moderate potentially bad outcomes caused by the very measures meant to save us.

All of this is to say, social distancing alone is not a sufficient long-term solution. It is definitely not sustainable without serious consideration of the long-term public health impacts and without consideration of additional safety nets that may be required to maintain distancing. This current round of social distancing is valuable only if we use it to use history and data to devise strategies for containment, treatment, and prevention. It will only work if we seriously re-visit societal safety nets.

Social distancing is only a valuable tool if we don’t allow it to create another, potentially bigger, public health problem.

“The pathogen destroyed half of Ireland’s potato crop, leading to rampant starvation and the death of nearly a million people.”

While the potato blight was clearly the proximate cause of the famine, it’s worth noting that Ireland was exporting enough food to feed its entire population to Great Britain every year of the famine. So in a sense the blight *plus* the colonial domination of Ireland by the British landlord class are together what led to those million deaths.