Bad Chart Thursday: Border Patrol Pads Assault Data to Falsely Claim Down Is Up

Assaults on Border Patrol agents have been decreasing for years, but as Debbie Nathan of the Intercept reported earlier this week, US Customs and Border Protection (CBP), in fiscal year 2015, started quietly padding the data enough to make a downward trend look like an increase.

Rather than assault numbers reflecting the number of incidents or officers assaulted, CBP multiplies the number of victims by the number of assailants and then by the number of weapons used.

As CBP spokesperson Christiana Coleman told Nathan: “An incident in the Rio Grande Valley Sector on February 14, 2017, involved seven U.S. Border Patrol Agents assaulted by six subjects utilizing three different types of projectiles (rocks, bottles, and tree branches), totaling 126 assaults.”

And just like that, 7 assaults, as measured by, well, everyone, including every other law enforcement agency, and even by the CBP prior to FY2015, becomes 126 in the new accounting.

CBP’s rationale for using this “new math”? Transparency.

Transparency, of course, explains why CBP never announced this change in methodology. Or why CBP spokespeople cite a percentage increase in assaults to the media, the White House, and when testifying to Congress, without ever explaining that the increase actually stems primarily from counting each assault as multiple assaults.

This self-professed transparency is probably why we’re all fully aware that no assault need take place for CBP to report an assault anyway. The CBP defines assault as “a physically manifested attempt or threat to inflict injury on CBP personnel, whether successful or not, which causes a reasonable apprehension of imminent bodily harm.”

This might explain why the Border Patrol focuses on the number of assaults rather than the number of actual injuries. Between 2006 and 2016, an average 11% of reported assaults resulted in injuries. (That’s my calculation using the FBI’s LEOKA data. The inflated CBP assault data would make the injury percentage even smaller.) Of course, an assault or attempted assault can be thwarted before causing injury. That doesn’t make it any less of an assault. But considering the CBP definition of assault includes simply fearing assault, any purported rise in assaults with a parallel low percentage of injuries suggests that there’s more of a rise in fear and misunderstanding than in violence.

Yet reports based on CBP’s jacked-up statistics understandably assume these numbers all refer to actual violence (e.g., Newsweek’s “Under Trump, Violence Skyrockets against U.S. Agents at Mexico Border, Officials Say” and, predictably, Fox News’s “Dramatic Spike in Violent Attacks against US Border Agents Provokes Outrage“), not to mention assuming that the number of assaults refers to the actual number of assaults.

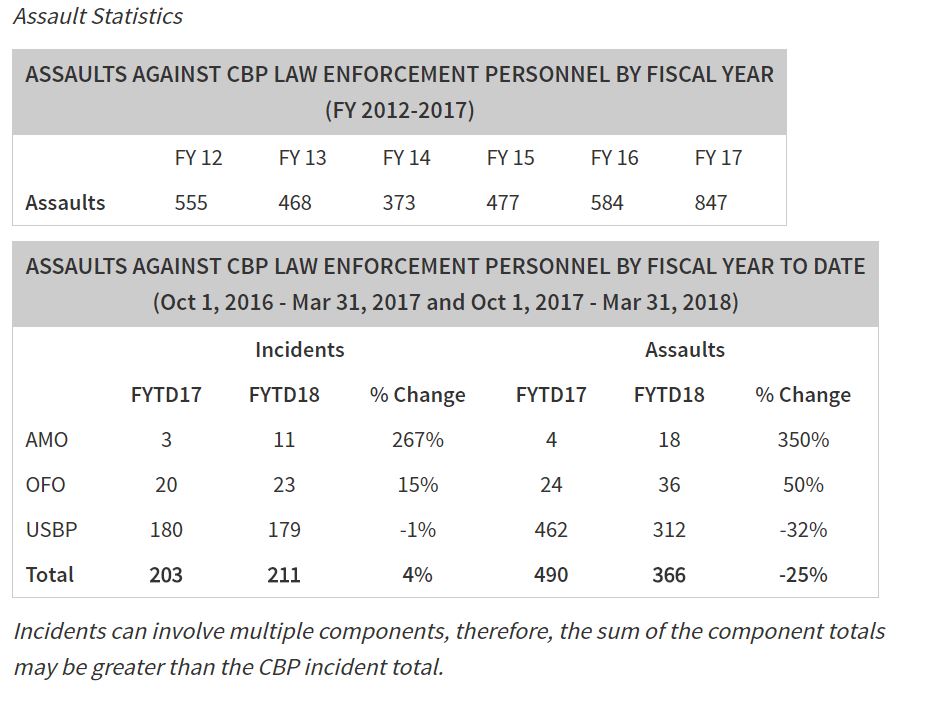

The one place I was able to find CBP mentioning this new methodology was on its Use of Force Statistics webpage, where these charts appear at the bottom:

The second chart, breaking down incidents and assaults separately, actually demonstrates the enormous difference the new accounting method makes, in this case turning a 4% increase into 25% decrease. But the chart showing total assaults from FY2012 through FY2017 makes no mention of the change in accounting that makes the last three totals completely incomparable to the first three.

The flawed and incomplete context on this page is still more than the zero context given by CBP officers and spokespeople when they cite the inflated numbers and skewed percentages to the public, including in testimony to Congress.

One of the first examples comes from testimony on November 30, 2016, from Mark Morgan, Border Patrol chief at the time, to the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee:

The men and women of the United States Border Patrol have one of the toughest jobs in federal law enforcement. They are the most assaulted federal law enforcement in the United States, more than 7,400 Border Patrol agents have been assaulted since 2006. That rose in F.Y. ‘16 by 20 percent, and year- to-date we’re seeing an increase in assaults up to 200 percent from the previous year to date. It’s a dangerous job. And since my short time here, two Border Patrol agents have already been killed in the line of duty, Agents Manny Alvarez and David Gomez.

Not only does Morgan not mention how much these percentage increases rely on multiplying each assault by alleged assailants and weapons, he seems to be claiming that a ten-year total (i.e., assaults since 2006) rose 20% in one year. Even the CBP’s inflated total for FY2016 (584) is not even close to a 20% rise from 7,400. He clearly meant a 20% rise from FY2015 (which CBP padded to a total of 477), but implying a 20% rise from 7,400 is just more of that transparency the CBP is claiming for itself.

The FBI’s statistics show 454 assaults of CBP agents in FY2015 and 484 in FY2016, which is an actual increase in assaults, but closer to a 7% increase than 20%, a small enough bump amid a years-long downward trend that, with the CBP’s DIY (Define-it-yourself) approach to characterizing assaults, doesn’t actually demonstrate that assaults are on the rise.

Oh, and those agents killed in the line of duty? The FBI stats for FY2016 show 0 agents killed. So I did a (very) little digging and found that David Gomez died from a heart attack while on bike patrol, and Manny Alvarez died in motorcycle accident with another agent. Was either agent included in the CBP assault statistics? It seems unlikely considering how obvious the causes of death were, but they were obvious before Morgan cited these men on November 30 as examples of how dangerous the job is because of assaults on officers.

The CBP’s dishonest portrayal of assaults against Border Patrol agents appears to be the rule, not the exception. Last June, acting chief of Border Patrol Carla Provost testified to the Senate Committee on the Judiciary:

Although illegal immigration is trending downward, assaults against Border Patrol agents are on the rise. In fact, Border Patrol agents are among the most assaulted federal law enforcement personnel in the country. As of June 1 of this year, Border Patrol agents were assaulted more than 550 times compared to fewer than 300 times over the same reporting period last year.

Are “Border Patrol agents . . . among the most assaulted federal law enforcement personnel in the country,” as Provost and Morgan both claimed? Are they basing that claim on the CBP’s doctored statistics? A look at FBI data for FY2016 (2017 data have not been released yet) shows 484 assaults out of 59,221 total CBP agents, which comes out to less than one assault (0.8) per 100 agents.

The Department of the Interior, with approximately 70,000 employees, experienced 621 assaults, or 0.9 per 100. (Considering how many of those employees are not likely to be in enforcement by any stretch, the odds of assault are probably even higher.) Even the 2,200 Capitol Police officers are more likely to experience assault, with 25 assaults in FY16, or a rate of 1.1 per 100.

CBP inflates the number for FY16 to 584 assaults, which puts the likelihood of assault at 1 out of 100, so even with those dubious numbers, working for the Border Patrol is still less dangerous than working for the Capitol Police.

And if we compare to nonfederal law enforcement, which in FY16 reported 57,180 assaults out of 586,446 officers, or 9.8 assaults per 100 officers, we can see why Provost and Morgan are careful to specify federal law enforcement.

So why is CBP being so dishonest in its portrayal of Customs and Border Protection officers as especially vulnerable to violence? The answer is clear in how this false information is being used.

The president of the National Border Patrol Council, Brandon Judd, has spoken to the media and testified in Congress to the need for more Border Patrol agents and increased prosecutions of accused assailants as a way to address the rise in assaults–a solution in need of a bogus problem to justify it. And indeed, last April, Attorney General Jeff Sessions told agents, “I have directed that all 94 U.S. Attorneys’ Offices make the prosecution of assault on a federal law-enforcement officer — that’s all of you — a top priority.”

And of course, these phony stats further the equally phony narrative of immigrants as criminals, with Vice President Mike Pence last March citing the rise in assaults as justification for spending billions on a border wall (which, incidentally, would not likely address the problem even if assaults were actually on the rise).

Of course, the Trump administration would pursue fact-free, damaging immigration policy regardless of whether the CBP provided false supportive data. The real issue here is that the media and Americans at large have clearly trusted the CBP’s stats as credible at face value. This makes us all amenable to drawing faulty conclusions about immigrants, Border Patrol agents, and border safety and security at the expense of immigrant safety and the potential to fix actual problems in our immigration policy.

The only rise in assaults CBP has consistently demonstrated is an assault on the truth. The organization’s dishonesty predates the election of Donald Trump, but the Trump administration’s consistent willingness to weaponize lies has turned an unethical practice into an actual threat to all Americans, who will have to deal with the ramifications of lie-based policies for years to come.

Featured image: ProtoplasmaKid / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA 4.0