You Are Not Burnt Out, Charlie Brown

This morning I woke up at 4:00 am, as I often do, and checked my phone. I popped over to Twitter and the first tweet at the top of the list read:

“Anyone else have burnout guilt? Like, I’m feeling very burned out but also… I’m not even working hard”

The term “burnout” has become my new pet peeve and these feelings of guilt and exhaustion are feelings I have been wrestling with for the past two years. I only started to find some peace when I realized that they are not entirely my fault. I started to be able to put names to what I was feeling after reading an article about “clinician burnout” published in 2019 at the same time I was watching my clinician husband become frustrated at the barriers that prevented ideal patient care. These authors ultimately define burnout as victim-blaming – as something that is inherent to the character of the person and an ultimate failure to not be able to push through. What many are feeling is not burnout. This is morale injury that has been perpetuated by the institution. Like clinicians, professors are often driven to academia by a strong desire to help. We want to advance new discoveries that make people’s lives better and help our students achieve their goals. Look at the parallels between health care and university life that show up in the first paragraph of that article alone…

“…practitioners suffer from rule-driven health care practices and distant, top-down administration. The demand for health care is expanding, driven by the aging of the US population.3 Massive information technology investments, which promised efficiency for health care providers,4 have instead delivered a triple blow: They have diverted capital resources that might have been used to hire additional caregivers,5 diverted the time and attention of those already engaged in patient care,6 and done little to improve patient outcomes.7 Reimbursements are falling, and the only way for health systems to maintain their revenue is to increase the number of patients each clinician sees per day.8 As the resources of time and attention shrink, and as spending continues with no improvement in patient outcomes, clinician distress is on the rise.” [Emphasis added by your not-so-humble author]

When the pandemic started, my kids were sent home for remote learning. My courses moved online. I found 10 people, all of a sudden, living in my house. I was teaching university seniors and graduate students, trying to keep my research going, comforting my older children, supporting my clinician husband, homeschooling my 2nd grader, and helping my brother and his partner adjust to being new parents. There were so many nights I laid in bed or on the couch and thought to myself, “I’m not sure I can do this another day. I’m not sure I can handle one more thing.” Yet, I kept doing it another day and kept adding one more thing. The low barrier to Zoom meant that my day was increasingly filled with back-to-back requests to meet.

My university brought us back in person with none of the protects that other institutions have had. No mask requirements. No vaccines. No social distancing. Just statements that “we’re all in this together.” I would walk over to the university hospital where they are allowed to have a mask requirement, 100 ft from my building, and see everyone dutifully masked. When I walked out the doors it was as though COVID-19 stopped existing. It was the wild west in my building. When I got COVID-19 twice, thankfully mildly the second time because I had been vaccinated and boosted, some folks generously offered to move our meetings online so that I could keep working while I recovered. How kind.

In December, I sat in my office and pondered why I was always so exhausted. I totaled up my efforts across my grants and teaching, added the expected 20% service expectation, and realized that I was far over 100% effort. I have a feeling I had a lot in common with that original twitter poster. I bet she’s working hard too. I bet that, like me, she doesn’t feel effective. When you don’t feel effective, you don’t feel like you’re achieving despite evidence to the contrary, and it makes you wonder if you should be working harder. The guilt becomes crushingly overwhelming.

Last month I had a revelation that broke the vicious cycle and started to allow me to start to find forgiveness for myself. I tweeted an admittedly cryptic tweet in a moment of exceptional frustration that my university was about to undergo some major changes and it was breaking my heart because I had really loved this place. People messaged me and asked if I was leaving. I had to admit, I didn’t know because my morale was so damaged. I really, really considered it. Now that the university has released the information publicly, I can share why I felt so injured. I mentioned in a previous post the issues I had with leaks in my lab. I had begged for help and, as I approached tenure, I realized that I needed to take control of the situation whether the administration was 100% on board or not. My husband Strange was generous enough to let my lab members work in his lab. They’ve formed a really great team but that lab is ~3/4 mile from my office. It takes a large chunk out of my day to get back and forth when I go over there and sometimes makes me feel less connected to the lab.

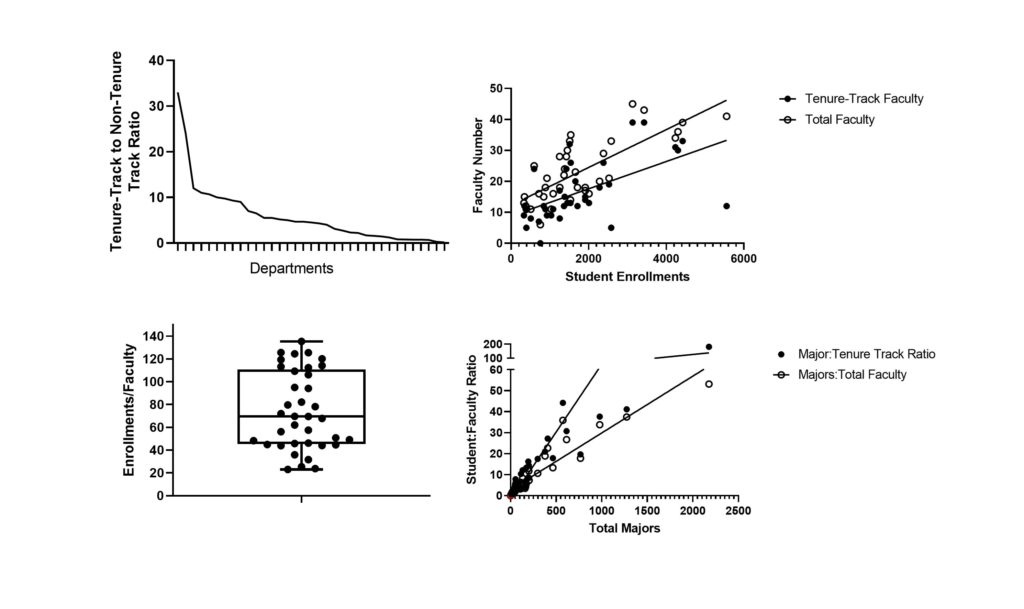

My university recently announced a major rebuilding project to support the needs of the hospital. They are going to tear down my building and build my department a bright, shiny new building. The downside is that it won’t have appropriate space for the work that I do, and a couple of other faculty. It hurt my feelings to see my colleagues dreaming about what the space could be, while feeling like an outsider despite my successes. Those were feelings I had to seriously work through. I wondered how much other disparity existed across my college. Being at a public university, most information is freely available. I did what any good scientist does best. I made some graphs.

That helped me crystalize the source of my morale injury. I was under the mistaken impression that reward and hard work are linked. I was under the mistaken impression that expectations are equally distributed and that the ideals of a university are what is practiced. These realizations have liberated me from the guilt I have been feeling. I don’t need to fix things that are not within my power and this place is not the source of my self-worth. It’s a place to work and to teach, but this is my job, not my priesthood.

The Chronicle of Higher Education published an article last month called The Great Faculty Disengagement where they described how many faculty haven’t left, but they’ve lost their enthusiasm. In a follow up last week, they asked

“If you feel disengaged, what would it take to turn your attitude around?”

One reader answered…

“My level of disengagement is healthier for me. Yes, this means I’m giving less of myself and my time to my students, but I think the boundaries create a clearer model of what working relationships should look like. I’m no longer considering the move up into leadership because of the frustrations of navigating institutional barriers and bureaucracy. I don’t want to become that bureaucracy.“

So, no Charlie Brown. You are not burnt out. You just tried to kick the football one too many times and realized that you don’t want to play that game anymore. Lucy hurt your feelings. Go fight the Red Baron with your puppy and get back to the things you love. That football is not for you and maybe Lucy should play alone for a while. She’s a bully.

Also, Rocco is not alive.

I think another casualy of the high patient to clinician ratio is the high COVID denialism and minimalism in US populations. I rolled my eyes every time I heard someone say “Talk to a trusted physician about whether you should get vaccinated.” How many people have physicians that would recognize them on the street?