Shakespeare in the Time of the Apocalypse

A popular question in fiction is, what would the world look like if society collapsed? Whether it’s through war, disease, famine, alien destruction, it all goes back to human nature. What happens to the survivors? Is Hell really other people, as the saying goes, or is Hell something else entirely? Also, what skills are valuable in the new post-apocalyptic world? Not everyone is a scientist, engineer, or very crafty farmer–there needs to be room for humanities and arts too, because survival is insufficient. That’s the basic premise of this month’s Skepchick Book Club pick, Station Eleven, by Emily St. John Mandel.

In Station Eleven, the Georgia Flu has killed off 99.9% of the population of Canada and the USA (we don’t know about what’s happened in the rest of the world but we presume they’re all dead too). It’s extremely contagious, and within 48 hours of having symptoms, you are likely dead. So there are two groups of survivors: those lucky enough to wait it out in quarantine and those immune to the disease. According to the survivors, the first few years after are bloody and terrible. Around Year 20, there’s a fragile peace in the air. Most survivors have started over by making small towns; some towns have elected officials, some towns are governed by committee–for the most part, people are good at their core and they want to help out and start over the best they can. Most people stay in whatever town they’re in, but in the middle of all this, a group of actors and musicians have banded together and they travel around performing Shakespeare (in exchange for food and goods) for each town. They’re called The Traveling Symphony and their logo is “Because Survival is Insufficient.”

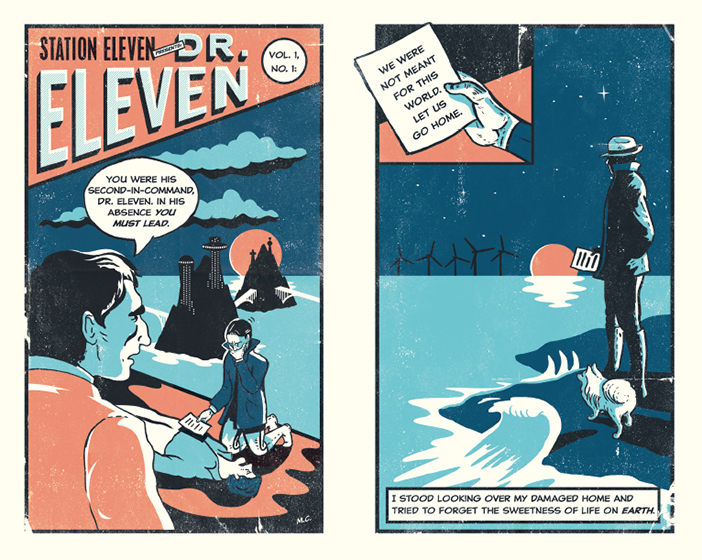

The timeline of the book jumps all over the place, weaving the past into the present, because the present is full of the empty shells and carcasses of the past. Most of the characters are linked to the same man: Arthur Leander, a famous movie star who died just hours before the epidemic started. His first wife, Miranda, was a struggling artist whose main project was a graphic novel named Station Eleven, about a planet that was turned into a starship that flies around the universe (and once you read the book, you understand why this graphic novel is relevant). There are only two copies of this novel, and one of them belongs to Kirsten, who was in a play with Arthur when she was a little girl. After the apocalypse, she carries around the comics and collects every tabloid clipping about Arthur that she can, in an attempt to hold on to her old life. And there are other characters too, but I won’t give away the whole story here.

As I mentioned earlier, most people have banded together and made peaceful communities. But as usual, there is at least one community that has turned into a cult, controlled by the Prophet (and his arsenal of weapons). He was a child when the apocalypse hit, and he and his mother survived because they were quarantined at an airport. She was a spiritual woman, the kind of person who probably had a bookmarked version of The Secret, so when the disease struck, she held tightly onto the mantra of “everything happens for a reason.” There must be a Reason why she and her son survived, and that turns into her son becoming a cult leader, preaching about how the virus was a perfect angel, sent to cleanse the world, and the only people left were the Chosen.

Conveniently, it’s also his mission to repopulate the planet, with as many women as he wants. (Funny how that worked out, huh?)

One of the striking things about the Traveling Symphony is that they only do Shakespeare plays. But how do people find these plays relevant in the post-apocalyptic world? The head of the Symphony mentioned that they had tried other plays, but Shakespeare was the only one that resonated with the people, and it makes sense if you think about it. Shakespeare lived in a time of plagues, and in a time before modern conveniences. It probably would be harder to watch a play where people were able to take clean water for granted, or turn on the TV, or use a cell phone.

Near the beginning of the book, after the flu kills everyone, there’s a whole chapter about the things that went away, a list of things that were no more. No more cell phones, no more taking pictures, no more knowing that you would survive getting a scratch on your finger, no more airplanes, no more unmanned borders, no more fire departments, no more anti-depressants. There are rumors in the present that someone has created a Museum of Civilization, preserving the artifacts of the near-past. Another character quips that the entire world has turned into a Museum of Civilization, because the rusted relics of the past are everywhere.

The only question I have for the author concerns a passage in the book where the Symphony travels past a high school and they go inside to check if there are supplies. One of the characters goes into the bathroom and finds a skeleton with a bullet wound in their skull. When they tell their friends what they found, one friend says, why did you go into the bathroom, when you know that all executions were performed there? And then that’s never mentioned again. Why was it a universal thing that executions were done in the bathroom? I guess it was because the bathrooms were at that point unusable but weren’t there any other rooms? And how did this become a fact in the post-apocalyptic world?

As a whole, the book was beautifully written, and the narratives wove into each other really well. This book took me a little while to really get into, but after I was a third of the way through, I became immersed in this world (and more convinced that I do not want to ever survive the apocalypse). Although if I did, I would probably develop an appreciation for Shakespeare and classical music.

Next month’s book: Redshirts

In June, we’ll be reading Redshirts by John Scalzi, and I’ll put a post up on Sunday, June 26th. (Or you can come to our live book club meetup in Boston (events are posted on our Facebook page).

I loved this book because so much post-apocalyptic fiction is about people tearing each other to pieces and this one is about people building something new. It is an essential facet of human development that as a species we have cooperated and I have always felt that this would continue to be the case in the face of near annihilation.

I liked that too, I thought the book was more realistic than other books because of how the characters were mostly just good people trying to make a new world. And I liked how the Prophet’s storyline just kind of ended in a non-cliche way. It was like a slice-of-life post-apocalypse book.

I liked the book very much. Well written. Well thought out for the most part.

I wish it had more of a payoff or since they mention 7 times that Shakespeare wrote King Lear during a plague which resembled a near apocalyptic event, that more Shakespeare thematic tie-ins to the current situations would happen. But still I enjoyed it and would recommend it.

To the question Mary (this article’s author poses), and sorry to sound morbid but high school (or other communal buildings) bathrooms probably became the universal or de facto rooms for executions (as in plural/many) because they are tiled and have drains for the inevitable blood loss of many people.

That is an excellent point about the drains and tiles! Consider the question answered.

I actually just finished this book yesterday without knowing about the book club. Glad it’s still getting attention. I’ve read a lot of post apocalyptic fiction and find the descriptions of daily life can easily run together. What really separates them is some theme or narrative structure. I really liked the idea of the Traveling Symphony and how so many characters were connected by Leander and the comics.

I’d also recommend the Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson which is an alternate history novel about a Black Plague that wipes out 99.9% of Europe allowing Arabs and Chinese to dominate the world. It covers about 1,000 years of history using the idea of past lives to explore things like scientific progress and how wars and politics echo our own timeline.

I’ve been putting Redshirts off for awhile, now I have no excuse but to bump it to the front of the queue.