Fairies as Atoms & Speedaway Electric Boots: The Fantasy/Science Mashups of Victorian Britain

We don’t think of science and fairy tales being particularly good bedfellows these days, but it was a popular trope in the Victorian era in Great Britain. In this week’s Science for the People episode, I spoke with Melanie Keene, a historian of science at the University of Cambridge, about her book “Science in Wonderland: The Scientific Fairy Tales of Victorian Britain”. In it she takes an in-depth look at a particular genre of science communication during the 1800s, which drew inspiration from fairly tale stories that were popular among children at the time.

We don’t think of science and fairy tales being particularly good bedfellows these days, but it was a popular trope in the Victorian era in Great Britain. In this week’s Science for the People episode, I spoke with Melanie Keene, a historian of science at the University of Cambridge, about her book “Science in Wonderland: The Scientific Fairy Tales of Victorian Britain”. In it she takes an in-depth look at a particular genre of science communication during the 1800s, which drew inspiration from fairly tale stories that were popular among children at the time.

The Victorian Era was a pivotal time for both education and science. The education system was undergoing vast changes including educating girls en masse for the first time, while science was increasingly shifting away from generalist hands and into more specialist realms. This was the golden era of refractor telescopes and the shift from “gentleman astronomy” toward astrophysics. Microscopes were being refined during this time and there was a growing demand for prepared objects for people to look at, with interest coming from both the scientific community and the general public. This interest resulted in a small boom in commercially prepared microscope slides, many mounted with colourful papers and lithographs.

A growing interest in the new and exciting science was not restricted to gentlemen academics: the middle classes were increasing in size, and with a combination of dollars to spend and leisure time to fill, were able to follow some of what was happening in the modern science of the time. Electricity was relatively new, industries leveraging the latest science were taking off, and there was an understanding among the public that a young brain marinated in modern science and engineering principles might go very far indeed.

This era is where fancy collides with facts, and rational thought begins to usurp magical thinking. It’s not so surprising, then, that fairy stories and science facts were blended together, using magical devices, settings and metaphors to engage young readers.

From Melanie Keene’s “Science in Wonderland”:

“These often quirky, usually charming, and occasionally dull stories were an important new way in which nineteenth-century Britons enthused about, communicated, and criticized the sciences. From nursery classics such as “The Water-Babies” to the little-known “Wonderland of Evolution”, or the story of insect lecturer “Fairy Know-a-Bit”, the fairies and their tales were often chosen as an appropriate new form for capturing and presenting scientific and technological knowledge to young audiences.

“Fairies and imps, dragons and demons, giants and gnomes, appeared throughout these texts: as framing devices, as storytellers, as starring characters, as illustrations, as the invisible forces of nature. They demonstrate how, for many, the sciences came to replace the lore of old as the most significant source of marvel and wonder, and of fairy tales themselves.

“Far from being the destroyer of supernatural stories about the world, through these fairy tales the sciences were presented as being the best way to understand both contemporary society and the invisible recesses of nature, since they revealed the hidden magic of both the sciences and of everyday life. But they also claimed a higher status: that their enchantment revealed the true wonders of nature. These real fairy tales of science were avowedly stranger than fiction. The history of the Earth, forces of the universe, inhabitants of a beehive, or contents of a drop of water, contained more wonderful characters and magical transformations than the most exotic lore of old.”

Our modern day understanding of dinosaurs, bacteria and viruses is so ingrained that we often forget how fantastical these creatures must have been when they were first discovered and placed into their correct context. One of the great things about interacting with young children today is getting to see this “return to wonder” first-hand again. Kids see the world the way we did when we first unearthed a T-Rex skeleton or peered through a newly created microscope to discover a whole new, much smaller world living right on top of the one we know so well. The world of science is often surprising, counter-intuitive, and mysterious: looking through a child’s eyes, science is magical. A magic we can pull apart and understand, but there’s a reason we respond with similar delight to a really well done magic trick that we do to learning a particularly surprising or fantastic piece of science fact.

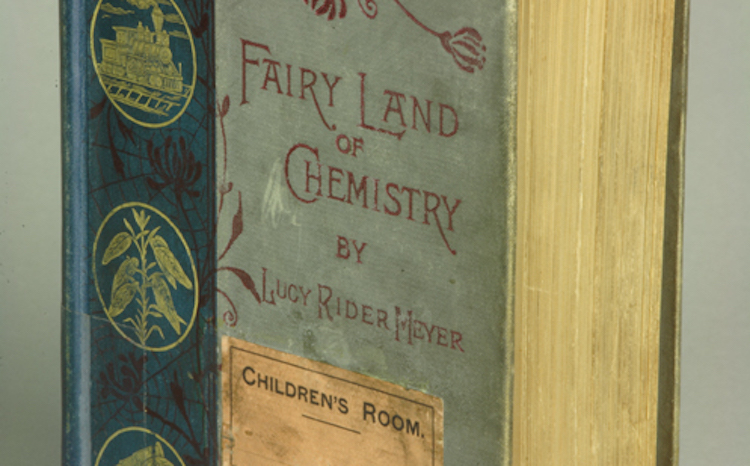

One of my favourite books that Keene talks about is Lucy Rider Meyer’s “Real Fairy Folks; Or, The Fairyland of Chemistry: Explorations in the World of Atoms”:

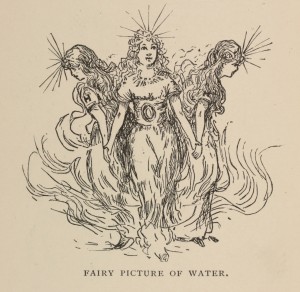

“Its central conceit was that atoms should thought of as fairies, whose behavior, dress — and even limbs — reflected their chemical properties. For instance, different groups of elements were sorted into ‘firms of fairies’ or ‘cousins amongst the fairies’, with similar properties.

The different states of matter were introduced as reflections of how active the fairies were. There was an emphasis on the ‘work’ fairies do in the world, for instance the use of chlorine in disinfecting hospital wards (where ‘a lot of Chlorine fairies’ were ‘let loose’) or in bleaching linens (where ‘a few men, aided by the tiny hands of the fairies, do in a single day the work that used to require thousands of workers and months of time’).”

Fairy atoms are depicted standing hand-in-hand together in molecules, and chemical equations are illustrated with mnemonic devices that implore the reader to make sure no fairy gets “lost” in the process, helpfully reminding you which fairy atoms like to stick together and which can’t stand to be near each other.

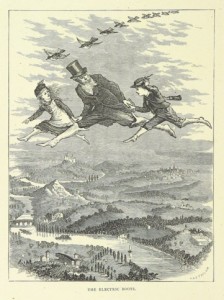

I also loved the travelling devices in Edward Forbes Winslow’s “The Children’s Fairy Geography”. In one section, he invites the reader onto his “wishing carpet” where the author would “cause our wishing-carpet to float so exactly over Scotland that the whole country shall be spread out under us like a map”. Later on, he creates “The Speedaways”, an updated pair of seven-league boots driven by electricity, styled with cutting edge technology of the day in mind, and inspired by world-shrinking achievements like the transatlantic telegraph cable which finally connected Britain and America together in 1858 and reduced communication time between the continents from 10 days to 16 hours. These magical devices used to communicate science in a novel way reminds me of a modern day equivalent, “The Magic School Bus” piloted by our beloved Ms. Frizzle.

Below are some additional Victorian Era stories that use fairy elements as devices or allegories to explain science to a young audience. I was somewhat pleasantly surprised to find a roughly equal gender mix among the authors of Victorian Era children’s science books: female authors are well-represented, and were well-respected as science communicators at the time.

- The Age of Monsters: The Fairy Tales of Science – John Cargill Brough

- Extinct Monsters: A Popular Account of Some of the Larger Forms of Ancient Animal Life – Reverend Hutchinson

- Episodes of Insect Life – Louise M. Budgen

- Fairy Know-a-Bit; Or, A Nutshell of Knowledge, by A.L.O.E. – Charlotte Mary Tucker

- Alice Down the Microscope – Agnes Catlow

- The Fairy-Land of Science – Arabella Buckley

- Life and her Children: Glimpses of Animal Life from the Amba to the Insects – Arabella Buckley

Featured photo by Gregory Tobias, from the collections of The Chemical Heritage Foundation.