Cross-post: The Perennial Problem of Gendered Dress Codes

Editor’s Note: This post originally appeared at Grounded Parents and is written by Cerys Gruffyydd. If you want to leave a comment, please click through the link at the bottom.

*****

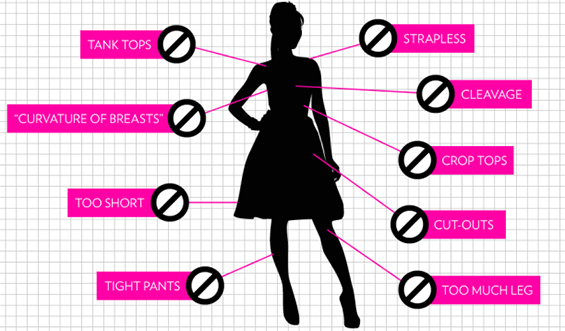

Recently I was chatting about dress codes with a friend whose husband is a high school principal. They were lamenting that he had been caught in the crossfire between (a) being required to write a dress code and (b) resentment that the resulting dress code treats male and female gendered students inequitably. He has my sympathy. I think that he probably did do his best in the circumstances. But. His students are correct, and they are not being hypersensitive, when they point out that the dress code hits female identified students harder than male identified ones. I agree that he has been placed in an unfair, no-win situation, but the students criticizing him are not the ones at fault, nor do they need to shut up. The students, themselves, are placed in an unfair, no-win situation by a larger culture that equates female-identified bodies with sex, while sex is a non-public behavior. The upshot is that female-identified bodies in public are, inherently, viewed with a certain degree of suspicion and unease. I’m not breaking any new ground by pointing this out, but the fact that this is still an issue means that people like me will still be bringing it up. Public school principals cannot single-handedly change society, but it is even more unreasonable to ask already vulnerable teens and tweens who have accrued less life experience, and are not in positions of authority, to do so.

My first elementary school (long ago, and in a conservative town) required me, as a girl, to wear dresses. This was a public school, and I was not permitted to wear trousers. I was a generally obedient child, so the worst I endured was being cold in the winter, and not being able to run full-out in PE, but that was about it. My older sisters were more rebellious, and they suffered to a greater degree from the dress codes. One, who was in junior high at the time, was sent home from school in very public disgrace for wearing trousers. She was not allowed back that day, and not at all if she was not wearing a skirt. My eldest sister was at the high school. She, as well as half a dozen other girls, were paddled by the male principal for wearing blue-jeans to school. These examples were extremely effective in reinforcing my own obedience. At six it’s easier to figure out which battles you cannot win, than how to fight back effectively. Part of the function of schools is to socialize children, meaning, in part, to get them to adapt their expectations and world-view to the larger culture around them. I’d argue that this can be problematic, particularly when done in a narrow-minded and dogmatic fashion (and the nature of institutional, bureaucratic rule-making lends itself to this.) It is especially damaging, however, when the socialization that children are being required to accept is built upon extremely contradictory assumptions. As my eldest sister pointed out “everyone” wore blue-jeans. In movies and advertisements she constantly saw women in blue-jeans. So what made it a punishable offense for her to wear them? Of course, the argument went that school was a more formal setting, and that blue-jeans were not appropriate. But boys were not paddled for wearing blue-jeans, and they were not sent home for wearing trousers. The issue was not that trousers were inappropriate, it was that our, female, bodies in trousers were seen as problematic.

a skirt. My eldest sister was at the high school. She, as well as half a dozen other girls, were paddled by the male principal for wearing blue-jeans to school. These examples were extremely effective in reinforcing my own obedience. At six it’s easier to figure out which battles you cannot win, than how to fight back effectively. Part of the function of schools is to socialize children, meaning, in part, to get them to adapt their expectations and world-view to the larger culture around them. I’d argue that this can be problematic, particularly when done in a narrow-minded and dogmatic fashion (and the nature of institutional, bureaucratic rule-making lends itself to this.) It is especially damaging, however, when the socialization that children are being required to accept is built upon extremely contradictory assumptions. As my eldest sister pointed out “everyone” wore blue-jeans. In movies and advertisements she constantly saw women in blue-jeans. So what made it a punishable offense for her to wear them? Of course, the argument went that school was a more formal setting, and that blue-jeans were not appropriate. But boys were not paddled for wearing blue-jeans, and they were not sent home for wearing trousers. The issue was not that trousers were inappropriate, it was that our, female, bodies in trousers were seen as problematic.

I’ve no doubt that a boy showing up to those schools in a skirt would have been dealt with harshly. This is part of the same enforcement of a gendered hierarchy, and can be horrible for everyone who doesn’t benefit from the framework. The value differential, male equated with better, and female with less-than, meant that the situation played out differently for boys and girls. Boys were not being  hammered with images of men in skirts, and being told that if they wore skirts they would be seen as stronger and better. Skirts were “feminine” and only someone who was willing (or forced) to be less-than would wear them. This was tragic for boys who didn’t identify as masculine, or who wanted to wear skirts, but the message was consistent, and boys did not show up for school in “girls” clothes. Girls, on the other hand, were being told outside of school, “you’ve come a long way, baby.” Virginia Slims was not the only company to subvert the women’s movement for commercial purposes, but that slogan perfectly encapsulates the impossible position in which girls found themselves. “Coming a long way” suggested that we’d improved over our mothers’ situation, and this “improvement” was represented by entering the “man’s world” and doing things that our fore-mothers had not been allowed (that word is important) to do, like smoking and wearing trousers. If we didn’t do these things we were weak and retrograde. But. We were still called “baby” and we clearly were not “allowed” to do masculine things in the formal environment of school.

hammered with images of men in skirts, and being told that if they wore skirts they would be seen as stronger and better. Skirts were “feminine” and only someone who was willing (or forced) to be less-than would wear them. This was tragic for boys who didn’t identify as masculine, or who wanted to wear skirts, but the message was consistent, and boys did not show up for school in “girls” clothes. Girls, on the other hand, were being told outside of school, “you’ve come a long way, baby.” Virginia Slims was not the only company to subvert the women’s movement for commercial purposes, but that slogan perfectly encapsulates the impossible position in which girls found themselves. “Coming a long way” suggested that we’d improved over our mothers’ situation, and this “improvement” was represented by entering the “man’s world” and doing things that our fore-mothers had not been allowed (that word is important) to do, like smoking and wearing trousers. If we didn’t do these things we were weak and retrograde. But. We were still called “baby” and we clearly were not “allowed” to do masculine things in the formal environment of school.

Click here to read the rest of this post or to leave a comment at Grounded Parents!