Let’s Talk About Gender Baby*

There’s been an uptick in discussions about gender theory in the atheoskeptosphere lately, and I’ve noticed a not insignificant number of people throwing around ideas about gender theory in ways that clearly demonstrate they don’t know what they’re talking about. Rather than wading into the specific discussions that have inspired this post, I want to try to clarify some key concepts in gender theory that I have noticed people misusing. For anyone interested, Veronica has written a post addressing how these concepts play out for trans people specifically.

NOTE AND A WARNING: Comments on this thread that are antagonistic rather than conversational and/or that try to bring in the specifics of any particular fight around gender theory will be deleted. This post is about gender theory in the general and is an attempt to clear up misconceptions. If you comment on this post, it better be in the spirit of clarification and scholarly discussion.

I should also note that this post is necessarily a gloss of many of these ideas, and that I am simplifying them in an effort to help clarify. There is, as usual, much more to these ideas than is in this post. But for our purposes, I am really only interested in clearing up misconceptions rather than writing a dissertation. If you want to delve deeper, I have included a list of recommended readings at the end of the post.

Let’s get started.

Essentialism vs. social construction

Often in the atheoskeptosphere, arguments around gender take the form of people fighting over “what is real,” which is usually premised on the unspoken assumption that something which has a material existence is “really real” and something that is socially constructed is “not really real.” This is a fundamental misunderstanding of social construction.

What does it mean that something is socially constructed? To say that something is socially constructed means that its existence is dependent upon social relations and the contingent meanings that we create. In other words, we construct it and give it meaning through our social actions. That something is socially constructed does not mean that it is “not real,” but rather that it is depends on social relations for its existence. There are plenty of things that are socially constructed that people consider to be real without questioning it such as money, marriage, national borders, and even language. Similarly, gender (and race and class) are social constructions—their existence arises out of and depends on social relations. So when someone makes the argument that “race is a social construction, it’s not real,” what they are actually saying is race is a social construction and it is not a meaningful biological trait for humans, which carries with it the hidden assumption that only biological traits are real (and, I have to note, saying race isn’t real can do serious damage as it can lead white people think that color-blind racial ideology is appropriate—if race is not real, why do I need to pay attention to it? But race is real, it is a real social category that affects people’s lives in tangible and biological ways).

In contrast with social construction, essentialism is the idea that each thing has a specific trait or set of traits that is required to be able to recognize it as that thing. In other words, there is some essential quality (or qualities) that define the thing itself. Under this rubric, for example, one might argue that marriage is the institutionally (church and/or state) recognized union of one man and one woman, and any other romantic relationship is not a real marriage because it lacks that essential characteristic.

From that example, it is clear that essentialism does not have to be biological. But gender essentialism most often takes the form of biological reductionism; that is, it reduces gender to one or a few essential biological traits. For example, a genetic essentialist view of gender is that a “man” has XY karyotype and a “woman” has XX karyotype. (I am setting aside the issue of the sex/gender distinction, and would encourage people to read up on the biology of sex because it’s not as clear as many people think it is. See recommended readings at end of post for some recommendations). Under this view, gender necessarily arises out of the sexed body; the biologically sexed body is indistinguishable from a person’s gender—they are either considered the same thing or gender is simply an expression of the sexed body. These traits are also usually viewed as immutable, meaning they do not change over time and they cannot be changed—they are “hard wired.” In this perspective, gender has an objective reality outside and regardless of how we make sense of it—thus, a “man” is a man regardless of how a person may identify as long as they have the essential (biological) traits of “man.”

It is no coincidence that many people within the atheoskeptosphere tend toward essentialism. After all, most people in these communities tend to highly value the natural sciences and think of science as a culture-free objective enterprise. Thus, the “soft” social sciences (and the non-scientific humanities) are often viewed as being wishy-washy and far less objective than the natural sciences, and so any theories developed in these disciplines are subject to increased, if not hyper, skepticism.

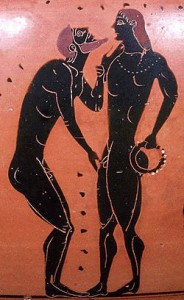

So we have these two camps that view the world in very different ways. How does this play out with gender? The example I use when teaching this distinction in anthropology courses is “gays in Ancient Greece.” An essentialist would argue that there were gays in Ancient Greece because there have always been men who are attracted to/have sex with other men, and we can see the evidence of these relationships in the archaeological record. Here, “gay” is used as a self-evidently simple word to describe any male-male same-sex relations. A social constructionist, on the other hand, would argue that “gay” is a historically and culturally specific term and that its meaning is not so self-evident; further, the forms of same-sex relationships between male-bodied people in Ancient Greece were not the same as they are in contemporary Euroamerican contexts. Those relationships were based on an active/passive understanding of sex and centered around age and status rather than gender. Thus, under a social constructionist view, there were no “gays” in Ancient Greece even if there were romantic and erotic relations between male-bodied people.

Ian Hacking argues that for people, unlike for (most) things, our categories actually bring into existence that which it names. So, whether or not Pluto is a planet (a socially constructed category) is irrelevant to the fact that there’s a giant ice rock floating around in space. That material thing will be there regardless of how we name it or categorize it. But the same is not true of kinds of people, which come into existence along with the categories we assign them. Thus, “gay” as a kind of person brought into existence with it particular modes of expression, of feeling, of identifying, which were taken up and further reproduced by people. To be “gay” is more than to be a male-bodied person attracted to another male-bodied person, as anyone who has experienced gay culture can tell you.

Performance vs. performativity

Gender, then, is a social construction. It is a way of categorizing people that is dependent upon social relations. But what is this construction based on if not on the material realities of sexually dimorphic bodies? Well, there are a few different ideas, but the one that makes the most sense to me—and the one I see being cited most often—is that gender is a performance. But what does this actually mean?

In her groundbreaking book Gender Trouble, feminist theorist Judith Butler laid out the argument that gender is performative. This is quite often misunderstood as saying that gender is like a stage performance—we put on costumes and act out our gendered characteristics on a social stage. But this dramaturgical understanding of performance is not actually what Butler was arguing.

Butler drew on J.L. Austin’s speech act theory and extended it to the analysis of gender. In speech act theory, language is not merely descriptive, but rather language is social and works to help people relate to one another. A performative speech act is an utterance that does what it says, versus a constative utterance, which is descriptive. We might better think of the “perform” part of “performative” here in the sense of “to carry out,” such as to perform a task. Performative utterances are thus not subject to true/false verification in the way constative utterances are because they are actions rather than descriptions.

So, for example, “I’m sorry” is a performative utterance because saying it actually does the act of apologizing. It is not a simple descriptive statement. You can disagree that I actually mean it, or you can reject it, but regardless of those things I have still apologized. On the other hand, if I say “the dog is brown,” that is a descriptive statement and is subject to true/false verification—me saying that does not make the dog brown.

Butler’s argument was that gender is performative in this sense. Gender is something that we do, an action or set of actions that continuously (re)enact, (re)inscribe, (re)produce, resist, reference, etc., the social meanings we attribute to bodies, behaviors, and ideas, rather than something that we are or have deep down inside of us. Gender becomes solidified or consolidated as a sense of self over time and space through our constantly citing/repeating of the social meanings (conventions, ideologies, etc.) associated with gender. In other words, gender is real because we make it real through our discourse—our language and our actions—not because there is some immutable and innate gendered self that we simply express through language and action.

So, what is gender?

Gender happens simultaneously at many levels. At the social level, gender is a socioculturally constructed system of organizing different kinds of bodies. The criteria that are utilized in the construction of such categories are culturally relative—the things that are emphasized as “masculine” or “feminine” or “androgynous” shift across time and space. At the individual level, gender is a socioculturally mediated identity that arises through discursive performances. This sense of self builds and strengthens over time, and for many of us it comes to feel as something natural, something we were born with and discover, rather than as something that has been and continues to be constructed and reconstructed throughout our lives.

To close, I want to make the important note that I am not trying to deny the material existence of bodies, and our biologies certainly play a role in our attractions, desires, physical characteristics, and so on. But those things do not produce gender; rather, as Butler argues, gender helps us make sense and meaning of those things. Thus, it’s not that any particular trait is biologically required for any particular gender, but that for each particular gender we have assigned particular biological traits to have more meaning than others. So there’s nothing about a body with XY karyotype, a penis, testicles that produce sperm, and higher levels of androgens that necessarily and inevitably equals “man” because the grouping of those traits is the result of a particular sociocultural milieu that is not true across time and space. And, in fact, we mostly move through our daily lives not knowing the truth of any of those traits about the other people we encounter. We assume, based on our gendered understandings of bodies, that some kinds of traits mean that all of those traits are present.

So how do we know if a man is really a man? Well, to paraphrase Susan Stryker, a man is one who says he is a man and then does what man means in his particular sociocultural context. I think what is at stake in many arguments against gender identity in the context of transgender lives is that people are contesting what “man” or “woman” actually mean. For many, a performative or constructivist approach to gender feels too flimsy and they want something more solid, more based in “nature” and the material world than it’s all a socially-agreed upon reality. But at the end of the day, that approach is still a social construction (haha, gotcha essentialists!), and such debates are part of the ongoing performative construction of gender.

Ultimately, gender is a complex issue and trying to boil it down to simple facts about one’s body obfuscates this complexity. I would hope that as self-identified critical thinkers, people within the atheoskeptosphere would drop the attempts at simplistic understandings of gender (and sex for that matter) and start making themselves be more comfortable with its complexity.

Recommended Reading

Here are some excellent resources on gender theory that I highly recommend:

The Social Construction of What? by Ian Hacking (not really about gender per se, but a great read for anyone interested in social construction theory)

How To Do Things with Words by J.L. Austin

The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction by Michel Foucault

Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud by Thomas Laqueur

Gender Trouble and Undoing Gender by Judith Butler

Sexing the Body and Sex/Gender: Biology in a Social World by Anne Fausto-Sterling

Gender: An Ethnomethodological Approach by Suzanne J. Kessler & Wendy McKenna

The Transgender Studies Reader by Susan Stryker & Stephen Whittle

A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory by Nikki Sullivan

Imagining Transgender: An Ethnography of a Category by David Valentine

Brain Storm by Rebecca Jordan-Young

Delusions of Gender by Cordelia Fine

Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex by Alice Dreger

Fixing Sex: Intersex, Medical Authority, and Lived Experience by Katrina Karkazis

Sex Itself: The Search for Male and Female in the Human Genome by Sarah Richardson

Masculinities by Raewyn Connell

Female Masculinity by Jack Halberstam

* Title of this post is shamelessly taken from the song Full of Fire by The Knife.

Something that I would add to the recommended reading is http://www.nature.com/news/sex-redefined-1.16943

This might be a bit close to essentialism, but the truth is that biology is not a science with hard and fast facts like the physical sciences. There is always a huge range of diversity and fuzziness to definitions and gender/sex is no exception.

As a physicist I can assure you that physics on the limits of our understanding is fuzzy as hell too. It has also turned out, time and time again, to be more complex than we first assumed.

Anyway, that is a good article demonstrating why not even on the biological level does the binary divide of humans (and other animals) into distinct male and female categories make any sense. In fact, throughout the history of biological research into the nature of sex, there has been a huge resistance to a simplistic view of sex as strictly binary and clearly defined.

But even if this wasn’t the case, policing how people live their lives in terms of the social structures we create would not be justified. We have created layer upon layer of gendered meaning into everything we do as humans, and these layers shift and change with time and across cultures. They are not fundamental at all.

Fair enough on the physics bit, definitely not my area of expertise.

And you are absolutely right that even if biology said sex was a strict binary it doesn’t justify policing people. I just like taking the biological argument away from them entirely. Essentialism is a deeply wrong idea, and it is wrong at all levels.

Oh, I totally agree that taking away the biological argument is satisfying in itself. :)

Thank you so much for this, I’ve really been struggling to get my head around it and this helps a lot.

So, then, what causes gender dysphoria? Why do transgender people report such strong discomfort with the sex they were assigned at birth?

I’m glad it helps!

To be honest, I don’t know what causes dysphoria. I’m not trans so I cannot speak to why trans people report such strong feelings. What I can say, though, is that there are many trans people who do not experience dysphoria, and even some of those who do resent their feelings being pathologized. As with most things it’s complicated.

I guess I would just say that dysphoria is a complex mix of social and biological phenomena and it is hard to tell what is sociocultural and what is biological. I know that’s not a great answer, but I think to try to give some simplistic explanation for dysphoria wouldn’t be helpful.

No, thanks, that’s a terrific answer. I’ve heard the argument that our brains are inherently gendered and that dysphoria happens when a person with a “boy brain” or a “girl brain” is born into the opposite-gender body. That seems wrong to me, but I’m still seeking out more information. The idea that “it’s complicated” actually makes much more sense to me right now.

If you want to read up more on brains and gender, I recommend Rebecca Jordan-Young’s book Brain Storm and Cordelia Fine’s book Delusions of Gender. You can find links to them on Amazon in the references list at the end of the post. =)

Thank you!

Well, as someone who is feeling what I, at least, would call dysphoria, I’d say what I’m feeling is an intense aversion to performing (in Butler’s sense) my assigned gender.

The thing is, gender performance isn’t like writing down a social security number or something. It includes what you have to like or dislike, how people react to you, the things you’re expected to do and put up with, and how you’re supposed to present yourself. It touches the core of who you are and your innermost nature — what you like and dislike and what makes you feel good and in tune with yourself and what doesn’t. And if the performance you’re required to do and accept based on your assigned gender just doesn’t fit with your nature?

I hope the following doesn’t violate Will’s stated limits on discussion here, but I don’t see how one can talk meaningfully about gender without talking about people’s lived experiences, and the only one I can talk about with any degree of authority is my own.

Being assigned male, I was expected to be rough and tough, to manage my feelings and the difficulties in my life with no help or sympathy, to hate girls and women and anything that was labelled “feminine,” to treat every other human being as a competitor who I had to beat. And lots of other stuff that I can’t even put into words. I can only describe it by saying that “being male” (at least what it means in USA society and especially the South, where I grew up) is simply contrary to my nature. It’s not a nature I got from society, since it was pretty much the opposite of what society was trying to brainwash me as. Having to perform “being male” was something I could force myself to do, sort of like forcing oneself to eat disgusting, rotten food because the alternative is to starve to death — but only to a limited extent.

I learned to live with it, more or less, but I always hated it and rebelled to the extent I thought I could get away with it. I also tried, on and off, to find some way of “being male” that was at all compatible with my nature. With no success whatsoever.

Ten years ago, I would not have called myself trans, even though I was allowing myself more and more gender non-conforming behavior. But at some point, I just gave up, and started saying that I wasn’t male, regardless of what I looked like. If you like, you could say I used to identify (however reluctantly) as male, and now I don’t. But you’d have to keep in mind that I haven’t really changed; all that has changed is what I call myself (and my willingness to try performing a different gender.)

Personally, I’m skeptical of the notion that we are born with a “male brain” or a “female brain” as such (since I don’t think that there really are such things) but based on my experience, I believe that we are born with certain psychological traits, tendencies, and predelections (i.e., our nature), and when the performance required of our assigned gender is contrary to those traits, etc., we’re going to have gender difficulties.

Thanks for taking the time to comment, that also helps me as I try to figure this out.

My thing is that as someone assigned female, I dislike that set of expectations and don’t want to have to conform to them, but the male role doesn’t seem to fit any better. I just want to be a person. I think gender as a concept is harmful to everyone, and we should be talking about how to dismantle that social construct, just as we should be dismantling race.

But I feel like I’m hearing some transwomen say that the category of woman is vitally important to their survival, and that people criticizing it as an idea are causing them real harm. I don’t want to do that, but I also don’t want the bars of my particular prison to be reinforced. Supporting the right of people to transition into whichever prison they find most livable is not the same as setting everyone free.

If we’re talking about transitioning as a short-term solution while we deal with the long-term problem, that makes sense to me. If we’re saying that gender is an innate thing that we must always have in order not to hurt people, I have a lot of major rethinking to do. So, like I said above, “it’s complicated” fits better with my current understanding of things. Thanks again for your thoughts.

Gender is a source of pleasure for many people, including myself. I think wanting to demolish gender per se is problematic, and instead we might be better served by focusing on destroying gender norms and hierarchies based on such norms. Gender should be a domain of free expression, not oppression.

If there are no norms associated with gender, what remains?

You may dislike the expectations that come along with being assigned female and maybe would even like to get rid of it, but from what I can see, there are plenty of cis women who feel it suits them well enough and, indeed, even revel in being (assigned) female. The whole “I’m so glad I’m a girl” thing. They may have some gripes about how they’re treated, but by and large, they don’t see being female as a prison. They would be incensed at the idea of taking their girl-gender away.

So why wouldn’t there be people who were assigned male who feel that the gender “female” suits them and want that gender to be available to them?

Even if you’re not one of those who think that the one gender construct or the other is just the cat’s pyjamas, living as one of the predefined genders is a lot easier than trying to get people to deal with you as having some do-it-yourself gender that nobody’s ever heard of. Among other things, if you can get society at large to accept you as a man or as a woman, there’s some hope that they will (mostly) stop looking at you like you have three heads and let you just get on with your life.

BTW, there is also body dysphoria, and though there are many theories as to where it comes from, none of them seem very convincing to me.

What I mean is that how gender is policed by people and society through the imposition of norms should be fought against; people should be allowed to do gender in whatever way they want without regard to what society considers to be the norm for any particular kind of body. I should not be policed into the gender “man” simply because I am male-bodied, I should choose to do gender that way or some other way or both. To insist that I not do any gender at all, though, also has the potential to be oppressive in the same way that insisting that people do gender in specific ways is oppressive.

That doesn’t really address my question, but I see that I’ve upset you, for which I sincerely apologize. Peace. I will look elsewhere in my attempt to reconcile my own desire for liberation with my desire to not interfere with the liberation of others.

Sorry, amm1, the “doesn’t address my question” part was because I confused Will’s last reply about gender norms with yours. The rest of my comment is still mean for you. Best wishes.

Thanks, Will, I think I understand your position now.

For what it’s worth, verbist, I understand where you’re coming from. It’s not an easy thing to reconcile. I do appreciate that you’re thinking about it and asking questions and talking about it, I think that definitely helps us all better understand, and hopefully therefore not marginalize or oppress, each other. ;)

“But I feel like I’m hearing some transwomen say that the category of woman is vitally important to their survival, and that people criticizing it as an idea are causing them real harm.”

While it may be a thing that happens, I’ve never actually seen this argument. What I DO see is the push to acknowledge that as long as the category “woman” remains in use, trans women have the same right to being included in it as cis women. IOW, as long as “woman” remains an existing gender category, trans women should never be treated as pretenders or people who “fake” womanhood; they should be treated as people who have the identity “woman”.

Excellent post. And, in my inexpert opinion, a lot of it also applies in all other contexts where we apply labels to ourselves and others, which is well worth considering when trying to make sense of people.

Dammit, I totally forgot to mention how offended I am at the illustration on the front page! Where are the puppy-dog tails? I demand puppy-dog tails!

Haha!

Thanks for this post, Will.

I would argue that talking about gays in ancient Greece isn’t necessarily motivated by essentialism. I can think of a variety of political motivations, such as wanting to disassociate “gay” from modern gay culture, to diminish the importance of self-identification, to emphasize the existence of a culturally-independent basis for same-sex behavior, or to advocate the adoption of the gay identity in other cultures. (Not sure all those political effects are desirable though.)

Hmm, I’m having trouble with this. How are those things not based in essentialism? Yes, obviously many people who claim things like “there’s a gay penguin” are not necessarily motivated by essentialism, but the underlying unspoken assumption of what “gay” means is still essentialist. What does a “culturally-independent basis for same-sex behavior” look like? I don’t think you can really do a culturally-independent anything when it comes to human behavior (and, I should note, you have essentialized “gay” here to mean “same-sex behavior”).

As you observe in the post, the essentialist definition is itself a social construction. It’s possible to advocate one particular social construction because it is politically useful to do so, and not because it is the “real” definition.

I oppose gender essentialism not just because it is an inaccurate descriptively, but also because that particular social construction is actively harmful.

Yeah, it’s a very complicated issue, for something that is, at its most simplistic, literally saying ‘there are two kinds of people’, and there’s a lot of cultural confusion because, what is gender? We know that gender identity has a biological basis, hence transgender people and cases like David Reimer. But how much does culture determine what we read into this?

But this is exactly what I’m arguing against in the post. Identity is a social construction, so if anything, the identities we build around gender (as a biosociocultural phenomenon) have a basis in culture. Butler, for example, argues that it’s actually gender that informs our understandings and experiences of sex, not the other way around.

But certainly the whole complex of gender, how people do it, how people experience it, how people express it, all taken together is a big biosociocultural mess, and it is pretty much not possible to tease out where one aspect ends and another begins.

Except that there’s still the obvious question about, you know, what happens when a boy is raised as a girl, such as in the Reimer case. Spoiler alert: It does not end well.

The Reimer case was undeniably horrible on many levels for many reasons, and John Money was terribly unethical in what he did to Reimer and his brother and family. But there are also cases where something similar happened and the person turned out to identify as a female. For a more detailed discussion about this, see Chapter 3 of “Fixing Sex” by Katrina Karkazis, linked in the recommended reading section.

But what is “identity”?

“At the individual level, gender is a socioculturally mediated identity that arises through discursive performances. This sense of self builds and strengthens over time, and for many of us it comes to feel as something natural, something we were born with and discover, rather than as something that has been and continues to be constructed and reconstructed throughout our lives.”

I am a man; I wouldn’t say that I identify as one. For me, the latter part of your statement is true: my internal state (my sense of self) changes dramatically. Part of it is due to the drugs I take for depression; part of it is due to an awareness of the research in cognitive science about how memory works and how we re-write our past experiences.

Good question. To be honest, I try to steer clear of using the concept of “identity” in my own work and prefer to talk about subject positions and subjectivities. But “identity” is what most people use, so I used it here.

But I guess at its most basic, identity is a person’s sense of self as they express and experience it. Identities are always sociocultural because they are formed in relation to others.

This is a totally contradictory statement. You identify as a man, then say you wouldn’t identify as a man.

Good discussion. Another thing I’d add to the reading list is the chapter on transgender kids in Far from the Tree, by Andrew Solomon. This and other material on children make it clear that the sense of one’s own gender gets going at a very young age. It’s complicated, because that internal sense doesn’t develop in a vacuum, but has something to do with both the body and the gender patterns a child observes in the world, from a very young age. However, at some point a person does have that inner sense which can be a sense of being male, being female, or being in between. This yields a competitor to your performance account. Why not say that a man is someone with the sense of being a man, etc. etc., instead of focusing on external statements and performances? This definition is a more liberating, I would say, as it allows that a person can be a woman, yet rebel against what society says about how women should be behave. And be a man, yet rebel against what society says about how men should behave.

Weird, I didn’t get a notification about your comment until this morning but it’s dated August 1. Sorry for the lack of response!

I don’t think what you offer is a competitor for performativity at all; in fact, what a performative theory of gender offers is that those “senses of being man/woman” aren’t inborn but rather come about through discursive practice.

To be honest, I’m not sure this is something can can ever truly be teased out. It is not possible to (ethically) raise a child without any interactions with other humans to see whether or not they develop gender absent any sociocultural influence.

Very good post

One thing I’d like to add is that you cannot not perform gender. Because it is a system of signifying practises, a system of symbolic representations. It is, in short a language. And currently it is a language where all people understand is 0 and 1. You cannot signal 3, or 1.5, or say you don’t signal at all. People will automatically try to understand either 0 or 1. Ambiguity is not tolerated.

Another thing is that we cannot know what a society without gender would look like or whether it is possible at all. We have no frame of reference, no way to imagine. But I guess that in 12th century France people couldn’t imagine a world where common or noble would cease to have meaning.

Will, I have to say this post is truly outstanding, and exactly the kind of 101-level explanation of contemporary gender theory I’ve been wanting for a long time. I have more questions to ask than I have time to write them, so I’ll have to just thank you for the post for now.

Thanks! I appreciate it and am glad you found it useful. I look forward to your questions when you find the time. ;)