I’ve written about the gender pay gap before and every time I do I get people who respond by insisting that there is perfect equality in the workplace and any imbalances that exist must be because women have different preferences and make different choices that result in them making less money in their careers. Anyone who has ever worked for a company that has discretionary pay and promotion policies knows that companies generally attempt to combat individual biases by emphasizing merit. In a perfect meritocracy, hiring, firing and pay decisions are made entirely on what a person does, not who they are. It makes sense that companies wanting to promote diversity without seeming to give unfair preference to minorities, would promote the idea of meritocracy, where every employee has an equal chance of succeeding regardless of their race and gender. Subsequently, if women or POC aren’t successful in a meritocratic system then it must be their own fault for not working hard enough rather than a system with built in biases that work against them.

A new study this week out of Cornell study from 2010 by Emilio J. Castilla and Stephen Benard (from MIT and Indiana University respectively) suggests that companies that promote meritocracy may actually be causing more bias against women and POC employees. Field studies have suggested that companies that endorse using merit to make personnel decisions do not close the pay gap between men and women and possibly even increase it. However, in the real world there are a whole set of complex interactions that determine personnel decisions, so it’s hard to really know whether emphasizing merit is actually having a deleterious effect on women’s careers and pay. The Cornell researchers instead designed a lab study that should be able to tease out the effect of emphasizing merit on personnel decisions.

Study participants were either MBA students with extensive work and managerial experience or current managers. Participants were given three performance evaluations, two with equally qualified individuals (one with a male name and one with a female name) and one evaluation of a clearly less-qualified individual (either male or female) in order to throw off the participants from realizing this was a study about gender bias. Prior to reading the evaluations, the participants were primed with a list of core values that either emphasized merit (“raises and bonuses are to be based entirely on the performance of the employee”) or did not emphasize merit (“All employees are to be evaluated regularly”). Based on the performance evaluations, participants had to make hiring, firing, promotion and bonus decisions.

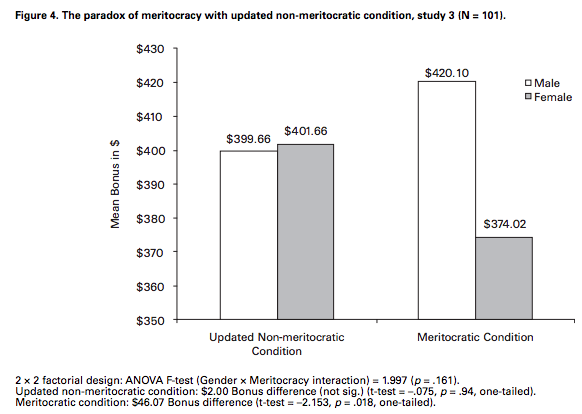

The researchers found that across the board, when participants were asked to emphasize merit in their decisions, they ended up being much more likely to treat the fake women employees worse than the fake men. Even though the women had performance evaluations showing they were just as qualified as the men, they were given lower bonuses, less likely to be hired, less likely to be promoted, and more likely to be terminated. It’s worth mentioning that the differences between the merit-emphasis group and the non-merit-emphasis group were not high enough to be statistically significant for hiring, promotion and termination decisions. It was, however, statistically significant in the amount of bonus dollars assigned to each employee. The researchers suggest that this may be because hiring, firing, and promotion decisions are generally public whereas bonuses are secret. Perhaps managers are more likely to consider diversity in their decision when they have to consider how the decision will look to outsiders.

This study shows clearly that priming a manager in certain ways prior to them making personnel decisions can drastically affect the results. Priming is a well-known and much-studied psychology principle in which a person’s decisions and behavior change based on something that s/he was recently exposed to. I’ve written about priming before as it relates to bias in surveys, wherein answering a bunch of questions establishing a person’s political identity may make him/her more likely to later answer questions about his/her beliefs in a more extreme manner. However, priming doesn’t always work the way we think it will. In this case, priming managers by giving them statements about being equal opportunity actually caused them to be more biased in their decisions.

As an explanation for how this could be possible, the researchers point to previous research that shows that when people think they are not being biased they end up making decisions that are more biased. In other words, recognizing that you probably have sexist and racist biases that affect your decisions and the way you treat the people around you, causes you to more carefully examine your decisions for signs of bias, which leads to less bias. However, a person that believes they are not sexist or racist is more likely to make biased decisions because s/he is not examining their decisions for bias.

The biases we’re dealing with in this case are clear. Men’s work is valued more highly than women’s work, even if the work itself is the same. This bias is so ingrained that when a person is specifically asked to make decisions only based on the work itself, a male name at the top of a performance evaluation results in a strong advantage to that person over equally qualified women. It is especially discouraging that emphasizing a focus on the work and not the person leads to more bias. Companies often emphasize merit because they want their personnel decisions to be fair and free from bias, but in doing so they may be disadvantaging the women and POC in their employ. Ironically, not mentioning merit at all may result in a more meritocratic system.

We see these same types of biases in non-personnel decisions, such as teacher discipline of racial minority students. Most people do not believe that they themselves could possibly be sexist or racist and this results in them inadvertently being more sexist and more racist. They would be better off recognizing their internal biases and actively fighting against them.

Human psychology is a funny thing and sometimes means that attempting to push someone in one direction can actually cause them to go in the opposite direction. The lesson in this study is that having good intentions does not always match with the evidence. Companies mean well when they enact feel-good policies like telling their managers to make decisions with a focus on merit, but the end result is that women and POC are hurt in the process. I don’t see companies changing their policies any time soon, regardless of how many studies like this one come out, but we can do a lot to change our own ways of thinking. It is only by admitting our own biases and actively questioning our own decisions that we can overcome them and perhaps reach a true meritocratic world where actions matter more than a person’s characteristics.

POSTSCRIPT: I want to take a moment to point how good this Cornell study is. I read and review a lot of research studies and for the most part they are pretty terrible, with researchers who are fishing for results or don’t quite understand the statistical methods they are using. This paper is one of the most well-done studies I have ever read with some clearly highly-competent researchers. These researchers clearly state their hypothesis and then explain how their test is designed to disprove their hypothesis. They then replicate their test two more times under slightly different conditions in order to remove any bias from their original test and confirm that the results hold in different settings. They also use a variety of different types of statistical tests and regression models to confirm that the test is statistically significant regardless of statistical test used. In other words, they do everything they can to attempt to disprove their results. The fact that their results hold and are consistent under this tough scrutiny gives me a lot more confidence in their results than I usually have in studies like this. This study is the gold standard for experimental research and other researchers should take note.

This study came to my attention via a post at Marginal Revolution

This doesn’t actually surprise me at all. Think about how you make an ambiguous decision in your life.

When you’re trying to be objective, and you find your options to actually be apparently equal, you make your choices more based on instinct.

Habit will be your primary driver. It’s not just discrimination that gets fueled by the impossibility of deep objectivity, it’s how people pick their breakfast, pick their shoes, their software. And in all those cases, the familiar wins. It’s easy on the brain.

>It’s worth mentioning that the differences between the merit-emphasis group and the non-merit-emphasis group were not high enough to be statistically significant for hiring, promotion and termination decisions.

Can someone please clarify for me what exactly this means?

It means that they were measuring responses for several different types of decisions, including hiring, promotion, termination, bonuses, etc. They found that their results on hiring, promotion, and termination did not disprove the null hypothesis, while the results for bonuses were statistically significant enough to overturn the null hypothesis.

If there is no statistically significant difference in the way study participants treated women for hiring, promotion and termination, then how can this be true?

Emphasis added.

For hiring etc. the difference was there but not statistically significant. For bonuses it was statistically significant.

It very well could be that I have a profound misunderstanding of the way scientific studies work, but I thought “not statistically significant” means a particular hypothesis cannot be proved using the data generated by the study.

The bias was enough for a significant difference for bonuses but not for hiring, promotion, firing etc.

Or basically what @Hanoumatoi said.

Jeez, I need to read down before replying.

It’s cool, I still love you.

“and one evaluation of a clearly less-qualified individual (either male or female)” — this is not accurate according to the report. They used the name Robert Miller for all of these ‘lesser’ qualified profiles.

Still interesting though. Would also loved to have seen an additional gender-ambiguous name profile thrown into the mix.

They used “Robert” as the name for the 3rd profile in the first round. In the second round they used the name “Linda.”

The meritocracy looks meretricious. (We should print bumper stickers, make T-shirts, magnets, coffee mugs…)