Does Ban Bossy Really Help Women in Tech?

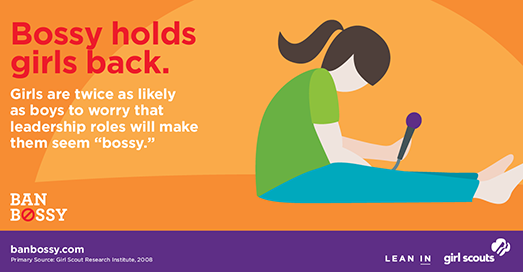

Over the past few weeks, you may have noticed your social media contacts affirming that they plan to “Ban Bossy.” This campaign, launched by Sheryl Sandberg’s LeanIn.Org initiative and the Girl Scouts, calls for us to ban the word “bossy” because assertive girls are labeled bossy and assertive boys are called leaders. It’s certainly a positive, well intentioned initiative that is sparking some good conversation. And it’s an easy way to feel good about doing good without doing much at all. But is it the right way to effect change? And is it doing anything helpful for women leaders right now?

Plenty of people have already pointed out the many issues with “Ban Bossy”:

It’s restrictive: “The movement for gender equality is at its best when it emphasizes expanding choices for everyone… Which is why it’s so frustrating to watch Lean In try to expand girls’ options by restricting the way we talk about them. It’s counterintuitive, and it makes feminists look like thought police rather than the expansive forward-thinkers we really are.” – Ann Friedman, NY Mag

It’s unrelated to the real issue: “…banning “bossy” also won’t eradicate the root problem that causes words like bossy and catty and bitchy to spread–mainly, that it’s common for leadership to be seen as a solely male quality.” – Jessica Roy, Time

It doesn’t address other expectations we have of women: “What I’m getting at is that the problem lies much deeper. Not matter what it ends up being called, assertive and demanding girls will have trouble being accepted because the expectation is to be kind, sensitive, and understanding.” – Andrea Stopa, Bust

It’s not empowering: “Instead of casting [bossiness] as a pejorative, we should be reifying the idea that being bossy directly relates to confidence, and teaching girls how to harness that confidence in productive and powerful ways.” – Danielle Henderson, Slog

Instead of banning bossy, we should think about how we can affirm women as leaders – specifically, bosses. Some organizations, like She’s So Boss and Women 2.0, actually make promoting female leaders their primary mission. And while the real work of recognizing women is harder to encapsulate in a simple two-word Facebook campaign, it’s also the indispensable aspect of creating a more equal culture.

Unfortunately, a recent development calls into serious question the extent to which big tech companies actually support women leaders. Julie Ann Horvath started working as a developer and designer for GitHub, a sort of social code sharing platform, in 2012 (gee, remember when we wondered why GitHub wouldn’t sponsor a conference about sexism and technology?). She took an active leadership role in encouraging women to become involved in tech, even organizing monthly talks from women in tech.

Late last week, Horvath revealed that she had decided to leave GitHub due to escalating and unresolved harassment from her coworkers and the partner of a company founder. You can read the depressing details here, but exactly what happened is not as important as the fact that abusive behavior was allowed to continue for far too long, and was not appropriately addressed by GitHub in time – or, really, ever (though the company has apologized). Of the situation, Horvath says, “My only regret is not leaving or being fired sooner.”

Is Ban Bossy something that would have fixed this? After all, Horvath’s beef is not being called bossy. It’s being directly harassed by her company founder’s partner. It’s having her code – her work – chipped away at by coworkers. It’s working in an environment where women hula hooping was cause for open ogling. Where a woman making contributions to the team is called “queen” (not, you’ll note, “bossy”).

But Ban Bossy is also part of a weird trend toward focusing solely on girls who might someday work in tech, not women who already do. It feeds into the notion that the only problem we face is obstacles for young girls, not abuse of women – or people – already in the space. One female programmer says, “You want more women in STEM? Start early,” even as she dismisses women’s-only events with, “To eventually eliminate sexism, it’s immensely important that we actually interact, compete and socialize with our male colleagues” – the familiar trope of putting the burden on women to end sexism.

Another longtime female programmer says, “Give me a young person of any gender with a hacker mentality, and I’ll make sure they get the support they need to become awesome,” but declines to do the same for adult colleagues: “It is not my place to drag grown women in chains to LUG meetings and attempt to brainwash them to make you more comfortable with the gender ratio, and doing so wouldn’t work anyway.” She also laments, “It was so much simpler when we didn’t analyze so much, and just trounced on mean people for being mean.” Many old-school female programmers also tend to reminisce fondly of the days when they were the only members of the special old boys’ club, and there weren’t so many other women knocking on the door – they’d actually like to go back to a time when there were fewer women in tech, rather than make an effort to get rid of the male-dominated culture that keeps women out.

When did sharing knowledge and showing respect become something we only did with children, not other adults? And why are programmers – those most analytical of people – seemingly so vehemently opposed to analyzing the implications of their actions beyond producing functional code?

We can’t get anywhere by pretending that professional women don’t face any obstacles, or (worse) that they somehow deserve the obstacles they face. We can’t pretend that Banning Bossy and investing in GoldieBlox will solve all our problems. That’s what creates situations where people feel they have to quit their jobs in technology because serious harassment is happening but isn’t being taken seriously. That’s what drives women out of technology even after they overcome obstacles to get there.

Last April, Horvath commemorated her first year at GitHub with some observations that seem to contain seeds of her current discontent. Among them:

People will disappoint you.

Too true. She also wrote:

Surround yourself with people who will push you toward the right answers, instead of tearing you down for not having found them yet.

It’s too bad that so many people in technology are tending toward the latter, when the appeal of technology itself comes so much from the former – a sense of exploration, wonder, and analysis. Not denial, distrust, and disappointment.

The problem I have with this characterization is that it is a false dilemma. The definition of the ideal leadership style for either gender is not bossy. There are multiple methods for leading people. Some are effective in small groups. Some are more effective for large groups. Being bossy is telling people what to do. It is based in fear and blame. Inspirational and collaborative forms of leadership avoid these mechanisms. Part of the problem is that we generate a lot of unethical followers that support authoritarian leaders.

From my perspective the simplest solution is to take these useful words that are culturally being used on predominantly one gender, and make an effort to encourage their use on everyone that the word applies to. To me bossy essentially means “a person trying using authority badly” (feel free to dispute) and from there how the person is being bossy is trying to use authority badly in different ways. After I saw this campaign I just decided that instead of banning it, I would watch out for situations where it applied to males and make an effort to use it when appropriate.

Someone on another blog made me rethink this one. If I go on continuing to use the word, even if I go around making sure I use it on men too that still reinforces the problems associated with it’s use on women in a broader context. I wish this stuff was easier to figure out.