On the Pulse of Mourning: Maya Angelou & Me

I owe an apology to someone who, as of this morning, will never be able to hear it: Dr. Maya Angelou.

A decade and a half ago, I was an adolescent attending secular public school after seven years of Islamic institutions. Our eighth grade literature textbook contained an excerpt from I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings: the chapter about Mrs. Flowers. As I had missed a few days of school in order to celebrate Eid with my family, I made a poster as make-up work, a garish mosaic-like collage comprised of bits of paper from a torn-up garden catalog, the pieces arranged to read “Mrs. Flowers”. I ended up picking up a copy of the book from the library and was enchanted. Eventually, I read everything about her and by her that I could find: poetry, articles, interviews, autobiographical novels.

Dr. Angelou eased both my barely-post-pubescent discomfort with other women and with my own emerging womanhood. My mother was an avid Oprah-watcher and so I was delighted when, after school, Dr. Angelou showed up on TV. I excitedly shared the parts of Dr. Angelou’s life that I knew would impress my mother as I noted the confidence with which the accomplished author carried herself. The confidence was reiterated to me when an older female cousin of mine discovered Phenomenal Woman. She asked me if I’d ever heard of “Maya Angeloo”; we spent an evening bonding over the frankly empowering words of the poem.

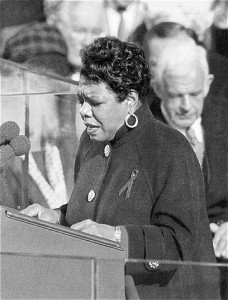

By the time I was on the cusp of adulthood, I had a much-cherished inaugural collectible copy of On the Pulse of Morning, could recite bits of her memoirs by heart, and had traced the words of Phenomenal Woman over my torso as I attempted to loathe my fat body a little less. Her works were among the 42 books proudly tagged as “favorite” on my Librarything account.

Then, a curious thing happened. Without thinking too hard about it, I untagged her works from their prominence among the entries in my digital library catalog, stopped referencing her as an influence on me, and gave away all copies of her works that I had — even the inaugural poem. My adoration of her went dormant, went quiet, practically stopped existing. I only realized it was still there when I choked up upon reading the news this morning. I wasn’t just mourning her passing, I was mourning my unabashed, unapologetic admiration of her.

I had gone from being a starry-eyed poet of a girl to a woman primarily interested in capturing the attentions of a certain type of man: intellectual, philosophical, atheistic. For many intersectional reasons, these men tended to be cis, heterosexual, and white. None of them would have thought to speak of Maya Angelou had they not seen my Libraything catalog or heard me mention her; she was readily dismissible to them. My role model was a token and a joke to these just-past-boyhood men, who called her trite, mediocre, overrated. They asserted that she was only a big deal because she was a black woman who wrote pretty words. They called her overly-sentimental in her reverence for womanhood and her celebration of love.

Raised in a sexist and racist culture and freshly uncloistered from a fairly isolated upbringing, I thought these men to be clearly superior to me in intelligence, and so I believed what they said. I set aside what I now saw, with the lenses that they had lent me, as childish, unsophisticated things. In the interests of impressing said class of men, I had become a woman who looked down on other women, who reviled femininity as weakness, who scoffed at the “hokey” nature of writers like Dr. Angelou. Of course, I simultaneously looked past the racism and misogyny of those True Artist™ white male novelists who wrote of cigars and whisky and their disdain for women. I hoped that valuing and devaluing the right things would make me an intellectual worthy of the respect of the men whose approval I so deeply desired. Instead, I became one of their “good ones”, trotted out in conversation as proof in order to counter any charges of misogyny or racism.

I slowly, painstakingly grew out of that and back into my admiration for Dr. Maya Angelou.

I am ashamed for those times I pretended to care less for her than I did just so I could attempt to impress someone for whom her work wasn’t (arguably, couldn’t be) as significant. I get the feeling that, if she were alive to hear my apology from me, she’d hug me and tell me that it was alright. She understood the contradiction inherent to being the type of woman who doesn’t really need a man but sure as hell wants men pretty badly.

I’m not ashamed of how weepily emotional I’ve felt all morning. “How like a typical woman,” sneer the young men I knew from my memory, and I curl my lip and sneer right back, that, in case they had forgotten what I’d forgotten for too long:

I’m a woman

Phenomenally.

Phenomenal woman,

That’s me.

<3

Miss you ladies! I really like what's happening on this site these days.