Islam 101: Botched Comparisons to Christianity

In my first post in this series, I broke down the basic, bare-bones definitions regarding Islam. In the comments, I compared a Muslim who doesn't believe that Islam is submitting to Allah's will to a Christian who doesn't believe in Jesus: they might exist, but they're pretty far from the mainstream.

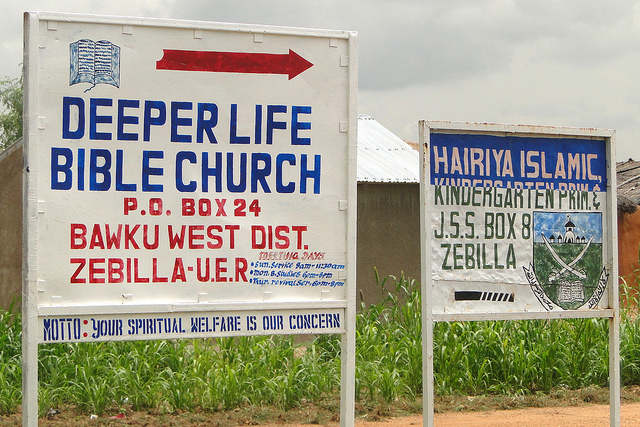

In Western countries, it's easy to try to draw comparisons between Islam and Christianity in order to attempt to understand the latter faith. After all, much of Western culture's understanding of religions stems from Christianity or, at the very least, is seen through a Christian lens. However, most of these comparisons could be made more precisely.

Muhammad in Islam is not the equivalent of Jesus in Christianity.

Christ is who gives Christianity its name; the fact that Muhammad's name is not part of the name of the religion he founded (unless you're an archaic-term-loving type) is significant. While Muslims are deservedly well-known for how they get up in arms (literally) over any perceived insult to the man, Muhammad is not the path to salvation for a Muslim. Belief in Jesus is what "saves" Christians. In the same way, it is sincere belief in the oneness of Allah (tawheed) that is most important in Islam, followed very closely by adherence to the Quran. On that note…

The Quran is far more important to Muslims than the Bible is to Christians.

Islam is a textually-based religion. Muslims take incredible pride in the (questionable) notion that the Quran has been kept in its original form since Muhammad brought it about. Unlike with the Bible in Christianity, where Christians see it as the word of God through inspired men, the Quran is considered to be Allah's direct word. There are Muslims who doubt what Muhammad was alleged to have said and there are Muslims who claim that religious practice is not as important as becoming closer to Allah, but you'd be hard-pressed to find any Muslim seriously claim that the Quran should be ignored. On the other hand, many Christians believe that Jesus's word and practice supercede anything said in the Bible, especially the Old Testament.

Love, at least as Christians understand the term, is not Islam's focus.

It is striking that this video refers to "Islamic love" in its description. Intentionally or not, the tagline plays into the notion that religions are about love, a notion mostly derived from understandings of Christianity. In many versions of Christianity, the focus is on loving and being loved, accepting and being accepted by Jesus. God is called "Our Father in Heaven" and forgiveness plays a prominent role. While Allah is said to love all creation in Islam and Muslims are ordered to love Allah more than anything else, the role of that love is far less, for a lack of a better term, mushy. The love is focused on respect and adherence; a Muslim proves her or his love of Allah through actions and is rewarded with Allah's love and blessings in return.

In a way, these differences in a deity's love mirror the differences in parental love between, broadly speaking, Western and Eastern culture. In the latter, a child is expected to show respect through obedience and be rewarded with parental pride and love, which in the former, unconditional love and acceptance are considered of utmost importance.

Heina, I think you’re splitting hairs when it comes to comparing Islam and Christianity when the real differences in religions often seems to be about the culture where the religion is practiced or originated. Clearly Islam is nothing more than an amalgamation of Judaism, Christianity and Middle Eastern Iron Age tribal religions; and Christianity is an amalgamation of Judaism, first century Judaic heretical groups, with some Egyptian, Greek and Roman religious and philosophical soup poured in the pot. I would think that Christians in Egypt don’t look or act much different than Muslims in Egypt, and how they expect their children to behave is no doubt pretty much the same as their fellow Muslim Egyptians. I would also doubt that absent any outside indications of religion a practicing Hindu would not look any different than a practicing Muslim in India in how they deal with their families. In the end for me it’s all about how your religious beliefs impact your behavior toward others that matters, and clearly religion of any stripe has the power to cause otherwise moral people to engage in immoral and harmful acts. I also respect that many of us in the west do not understand Islam that well; and from my perspective as a former Christian I can say many people in the skeptical/atheist community ignorantly think all or most Christians are conservative, fundamentalists, evangelicals, creationists and misogynists, when pathetically it’s those types’ of believers who are simply the loudest and most noticeable.

I both agree and disagree.

I agree in that, for most people who grow up in a religion, especially in the dominant religion of their area, there is no clear distinction between religion and custom. Minor details of Religious observance take on the force of custom and come to be seen as essential. They then acquire additional customs like a boat acquires barnacles, until pretty soon nobody remembers what is boat and what is barnacle. That’s how I remember growing up in the Episcopal church — having your shoes polished was as important as knowing the prayers. (Understanding them was, of course, unnecessary.)

But I disagree in that the essence of Islam is quite different from the essence of Christianity.

The essence of Islam, as I understand it, is submission to the will of God (Allah). The name “Islam” basically means “submission” (hopefully Heina will correct me if I’m wrong.) The focus of the religion is on what Allah requires of you, starting with the Five Pillars of Islam.

By contrast, the essence of Christianity (ever since Paul founded it) is redemption, of God sacrificing himself to save his people (however defined), from whatever consequences being bad brings you, which we all need, because we are all bad. Nobody is so good that (s)he doesn’t need to be saved, and nobody is so bad that (s)he can’t be saved. The central ritual — communion — is about partaking of that sacrifice, and the prayers and rituals are about reminding people that they were going to suffer those consequences but now they aren’t, because of God/Jesus.

Historically, this has led to huge differences. Christianity’s emphasis on the afterlife has AFAIK no counterpart in Islam, for instance. AFAIK, Islam has not had schisms and holy wars over differences in theology.

If you think that there has been no schism in Islam, you are completely ignorant of the history of that religion. Shi'a and Sunni are the same? Adherents of both get together just fine? Riiighht….

Do you also think that the Christian Bible might have errors, but that the Qur'an is direct dictation of Mohammed's words, with no human intervention or error?

First of all, I was addressing Islam and Christianity as theological constructs, not necessarily as practiced. That said…

Of course these religions were influenced and are influencing each other. That doesn't mean that pointing out their distinctions is "splitting hairs." Theologically speaking, there are major differences.

There are some major, major differences, actually. Egyptian Christians and Hindus in India drink, which is taboo for Muslims. Muslims from India especially will talk about how "those Hindus are all drunkards" and so forth. I wouldn't dismiss the importance of religion in people's lives.

I wasn't addressing this, just the theology. I think it's rather unfair to accuse me of splitting hairs when what you're saying is outside the scope of what I was trying to say.

Agreed, and this is why I write about Islam. Not to split hairs, but to educate. I hope I do that occasionally (;

I would point out that one major reason some people called the religion right in the US the "US Teliban", isn't just that some of the stuff they want to force on people is similar, but because many of them presume that "fear of god" trumps silly rules, like loving your neighbor (or they redefine that as, "saving them from themselves, by forcing the Bible on them), and the Bible is "inerrant". They may be more willing to allow that the Bible has changed over time, but they believe those changes have been "purification", and restoring it to some truer state, as God intended.

So, you might argue that their is no obvious equivalent of the, "Jesus is more important than the OT", in Islam, but the biggests wackos on the block in Christianity are only against Islam, on the princimple that because its using the wrong book, not because they think absolute obedience to their god isn't the "corner stone" of their faith. If they could get over than one minor thing, and the need for some sort of enemy to rant against, when they don't have anything to say about liberals that week, they would all be comparing notes of just how important prayer rugs really where, compared to candles, and which minority they hated the most. The distinction is purely a societal one, imho. Without those secondary influences, pushing Christians to at least play lip service to the idea that they value things which fundamentally contradict their own assertion about absolute obedience, there wouldn't be much difference. As it is, such hard liners are about as consistent with either what they believe, vs. how they have to act to not seem completely nuts to everyone else, as some guy on a mountain claiming he hasn't eaten anything more than leaves in 50 years, while thanking the guy that just brought him a 3 course meal, as tribute.

But, even that inconsistently, all too often, is part of a, "Love thy neighbor means the people just like me, I can lie, cheat, steal from, etc., everyone else, for their own good, and my own salvation and reward.", thinking. They have said as much, when caught unawares.

Heina, two things:

1) Very well done, fun to read, and informative. As usual.

2) We miss you. When do we see you next? SkepchickCon, I hope :).

I will indeed be there. I am quite excited.

Overall, I enjoyed your comparison.

But I was brought up Catholic (by a REALLY strick Catholic mother). Although I never believed, I was forced to practice until I was 17 years old.

Your description of love in the Islam faith is pretty much exactly how I would describe it in the Catholic faith.

That's a very good point. There are factions of the Christian faith, especially Catholic ones, where practice is emphasized and a stern God is the deity.

I really like your Islam 101 posts. They are very informative, and you have a rather unique perspective.

Seconded. I would add that i greatly appreciate the slow and steady pace you’re taking. Commenters occasionally seem to jump ahead to the more fun (and perhaps more contentious) cultural / sociological aspects, which i’m also looking forward to, but i (like many, i think) need time to digest these “very basics”.

Heina,

Great Work, I really enjoy your stories on Islam.

Heina–

I asked this before, but maybe it got lost. It's about the distinction between sin and evil.

Christians tend to conflate the two. When most Christians discuss sin, they usually aren't making the distnction between a sinful act and one that is actively harmful.

For Jews, the distinction is much sharper. There really isn't much of a hell in Judaism anyway, but generally, while most Jews would agree that eating pork, say, is sinful, I don't know many that would call it "bad" — or evil, anyway. The dietary laws are all about expressing your identity as a Jew, of making that distinction between tribe and not-tribe. (It's one of the reasons given for the taboo on tattoos, though there is a lot of debate there). The expression of faith, the behavior, is what matters there.

Christians seem to have left off the dietary laws (unless you are a Seventh Day Adventist). I was curious as to how Muslims draw these distinctions. You touch on the isue of adherence, but that only gets me to part of the answer, if you see what I mean.

I ask this because to me the big similarity betwen Islam and Christianity, at least in a theological sense, is that you aren't born into it. Christians have baptism, (is there an equivalent in any strian of Islam, besides profession of thre faith?) for instance. You can convert to Islam. Jews are born, not made, though you can convert it isn't exactly encouraged like it is in Christianity or Islam.

Also, to your point about love: Most protestant sects do emphasize a pretty stern and bad-ass version of God. Just listen to any Baptist sermon (especially in an SBC-affiliated church). While for Christians there don't seem to be as many "ritual" things to do (like the Jewish Sabbath prayer or the Islamic admonition for daily devotion) there is a very strong streak of prohibitions on gambling, drinking, and things like that, emphasized with visions of hell. I'd argue that Protestant (and specifically, Calvinist) influence is what makes Christianity rather different in the US from Europe.

I'm sorry, paragraphs seem to be problematic here :-(

It's a very common issue because what you see is not what you get. To create a paragraph, use a double line break instead of a single. It'll look weird in the editor but come out correctly on the other side. (The single line breaks are not actually discarded, but they get translated into an HTML break tag which is not what was intended.)

Ah ha. thanks.

There are two things I have to say. First I love these posts. I understand they're hideously oversimplified, but it's nice to have a basic knowledge of what's going on theologically in Islam. In some ways that information isn't terribly useful, because the things people actually do in the name of their religion doesn't change much regardless of their theology, but it does change how they do it.

Second, I love how the sponsored ads change completely for the Islam 101 columns and the other Skepchick content. Apparently the sponsors thought this column appealed to actual Muslims earlier today, because a Muslim dating site came up. Currently it's Bible College.

Hey Heina, I thought you (or anyone else interisted in these things) would enjoy this article in the current issue of History Today. It’s a subscription publication but some articles are available for free and fortunately this is one of them!

http://www.historytoday.com/tom-holland/islams-origins-where-mystery-meets-history

Partly, I think your understanding of how religious doctrine develops is somewhat questionable, but part of the problem here is also that you're conflating muslim theology with the cultural realities of parts of the traditionally muslim world, specifically the cultural realities of the modern Arab Near East and of modern Pakistan and north India. In point of fact, if other traditionally muslim communities (or these same regions in days of yore) were contemplated as the focal point of the understanding of Islam, a very different set of traits might (and, well, probably would) emerge.

Regarding one of your comment-responses:

Of course these religions were influenced and are influencing each other. That doesn't mean that pointing out their distinctions is "splitting hairs." Theologically speaking, there are major differences.

I don't think you're splitting hairs. I think you're misconstruing what theology is, and in a way that actually empowers religious nutjobs. I would argue that it is a mistake to discuss "just the theology" as if it too were not culturally and temporally bound, and therefore a participant in and a product of the same kinds of interactions and influences that operate on any other aspect of a religion -or indeed culture in general. It is an unfortunate (for everyone except salafis) and rather peculiar assumption that every important aspect of Islam has always been, or always "should" be (to a believer), dictated by scripture and prophetic sayings. In fact, historically, the Sunna and the Qur'an have not simply served as dictators of attitudes, beliefs, values institutions, but rather as a filter through which pre-existing values, ideas and institutions are either accepted or rejected i.e. assessed with the spread of Islam. There is no such thing as an unstoried, cultureless religion. I cannot shake the sense that you're conscripting a heavily parochial understanding of modern, post-colonial (purely in the temporal sense of the term!) Sunni orthodoxy/orthopraxy as a reductive stand-in for Islam as a whole. In doing so, you are in effect doing e.g. Yusuf al-Qaradawi's work for him.

By way of example, let's take the bit on the different conceptions of love. You begin:

Intentionally or not, the tagline plays into the notion that religions are about love, a notion mostly derived from understandings of Christianity.

Perhaps, but that is a historical accident and not due to any peculiarly Christian notion. Christianity has had more than its fare share of influence on religious thought over the past 2000 years for better and (mostly) for worse. But the idea that religions are bound up with (or even are love) is hardly uniquely Christian. It was Jewish Rabbis who read erotic allegories into the Song of Songs, a book included in the Hebrew Bible at least 300 years before anyone called him/herself a Christian. It was the pre-christian Greek Plato who (look it up in Phaedrus 249d-257b), elaborated the notion of love as the best kind of divine possession and of divine love as the only kind worthy of praise. It was medieval Hindus who gave the concept of Bhakti much of the form and meaning it has today. While hardly a cultural universal, the desire to see belief in the powers almighty as a form of love is too widespread for Christianity to get the credit you give it. Speaking of which:

In many versions of Christianity, the focus is on loving and being loved, accepting and being accepted by Jesus. God is called "Our Father in Heaven" and forgiveness plays a prominent role.

O like it doesn't play a prominent role in Islam? One could quote the Qur'an and medieval Islamic thinkers up the wazoo in the service of argument/pedantry here, but I think an astaghfirullah! or two will make my point clearly enough.

While Allah is said to love all creation in Islam and Muslims are ordered to love Allah more than anything else, the role of that love is far less, for a lack of a better term, mushy. The love is focused on respect and adherence. A Muslim proves her or his love of Allah through actions and is rewarded with Allah's love and blessings in return.;

This is completely untrue for most forms of Sufism (which, until the reactionary backlash against it, was far more widely professed than most people realize,) and largely untrue for many other devotional and/or regional articulations of Islam more strongly influenced by Sufism. For example, the idea of God-as-Beloved in Islamic Persia was (and indeed, for many, still is) of such overpowering appeal that even descriptions of human sexual lust could take on a divine flavor. From the late 13th century until the colonial period it was scarcely possible to write a love poem in Persian without it reverberating with the divine/mystical undertones forced on it by the God-as-Beloved cliché (unless one got really graphic or bawdy.) Hell, even a rather skeptical and unorthodox fellow like Hafiz could write religious poems loaded with such commonplaces . The wealth of textual as well as material evidence from e.g. medieval Andalusia also suggest that this was part of a wider pattern in the muslim world. c.f. folk such as Ibn Al-Arabi, Umar ibn Al-Farid and the earlier Rabi'a Al-Adawiya. Indeed, the somewhat aescetic and god-lovelorn aspects of Sufism in fact suggest that scripture can in fact take a back seat to the formation of theology at times. The fact that the Qur'an speaks of a ??????? ??????? ?? ??????? ????? "a monasticism/asceticism which they innovated, which We did not prescribe for them" certainly didn't stop things such as Sufism until, for other cultural reasons, its denouncers gained the upper hand. c.f. This video

In a way, these differences in a deity's love mirror the differences in parental love between, broadly speaking, Western and Eastern culture.

Oh for the love of god (pun intended.) Seriously? Eastern culture? Like Indonesians or Uyghurs belong to anything remotely approaching the same culture ("broadly speaking" or not) as Turks or Indians. You know much better.

In the latter, a child is expected to show respect through obedience and be rewarded with parental pride and love, which in the former, unconditional love and acceptance are considered of utmost importance.

By that standard, the (Christian!) Bible-belt is Eastern and (Muslim!) Bosnia is Western. And what of black American muslims? In a discussion such as this it seems to me to be downright absurd to ignore the influence that Christianity and Islam have had on one another over the past millennium or so, and to take as axiomatic -when the issue is raised in the comments- that dogma and theological fundaments somehow develop in a cultural vacuum.

This is not to deny that there are important ways in which Christianity and Islam differ, or that much of the other stuff you've said is in fact true. But context matters more than I think you're allowing.

To take a diachronic example: as I have mentioned to you before in another medium, nowhere does the Qur'an or the Sunna specifically require the non-Arabophone muslim to pray in Arabic. None less than Abu Hanifa once issued a judgment to the effect that saying Al-Fati?a in e.g. Turkish or Persian was permissible. (At the time the format of prayers had yet to be standardized mind you.) There seems to be some research suggesting that Abu Hanifa later changed this to say that reciting prayers in non-Arabic was only permissible if one did not know Arabic. Even if he did, my point remains: I have yet to meet the non-Arabophone urdu-speaking Hanafi who is even aware that they could even have the option of reciting prayers in a language they understand. Would you not say the saying of prayers in the language of scripture is a theological matter? One which btw sets Islam apart from Christianity (which developed and sacralized one liturgical language after another as with e.g. Greek, then Latin, then Church Slavonic, Coptic, Syriac etc.)? This is part and parcel of Islam, yet it owes little to the Qur'an and the Sunna, so much as the medieval Arab supremacism which preponderated until the shu'ubi movements put that narcissism in its place. (Consider how the various notions we associate with the word "Church" owe less to scripture than to the enfranchisement of Christianity as a state religion.)

Incidentally I would say that the relationship between believer and God's law, (and issues attending to Shari'a) are probably more fundamental and scripturally salient than concepts of love. Even these, however, are storied and context-sensitive, owing not just to the fact that Muhammad lived to be a political leader of a large community which grew into an expanding empire, whereas Jesus died long before his followers were numerous or organized enough for him to care about shit like who inherits what, but also the fact that Christianity ended up developing in the context of a crumbling empire too insecure for legal pluralism, and an old social order that took a much longer time to die/be subsumed. Yet even this historical theological and developmental difference didn't stop the Church Fathers from issuing fatwas on whom you can fuck and in what position.

You are desdcribing, fairly accurately, one huge reason why the non-religious find religion "in general" problematic. It literally shifts with the wind, and if the wind is a breeze, and carries the sent of flowers, all well and good, but it can just as easily be a tonardo, dropping anvils. There is nothing in the faith itself which can define which of these winds it should be blown by, or help the follower tell when they should be sniffing the wind, instead of dodging anvils. In fact, there is bound to be someone, someplace, who insists that flowers are a problem, and the smell of anvils is what should be encouraged (usually dropping on someone else, of course).

I like this series very much. But I was wondering if you planned on discussing the Sufi's?

Thanks for the post!

Andrew Walls made a great insight that is helfpul for thinking about Islam and Christianity, "Much misunderstanding between Christians and Muslims has arisen from the assumption that the Qur’an is for Muslims what the Bible is for Christians. It would be truer to say that the Qur’an is for Muslims what Christ is for Christians" (The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History [Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2002], 29).